Australia & East Timor

A Tale of Oil and Exploitation

by Vinita Ramani & Kathy XuEast Timor is a young, impoverished nation with natural resources in its backyard. But Australia has benefited for decades from drilling for oil and gas in the Timor Sea instead. In 2018, the two countries signed an historic maritime boundary treaty, finally determining that the Greater Sunrise fields belong to East Timor. Will Australia repay what it owes, and is China going to play a role in developing the country’s oil and gas sector?

The Greater Sunrise fields is a collective name given to the Sunrise and Troubadour gas fields in the Timor Sea. Discovered in 1974, the fields hold an incredibly rich amount of oil. Under a joint-venture, four companies—Woodside, ConocoPhillips, Royal Dutch Shell, and Osaka Gas—operated the fields. Due to prolonged disagreement over the boundaries of the fields, it has been underdeveloped.

Map of Timor Sea, East Timor and Australia with maritime boundaries and the oil and gas reserves. Source: IMF/WB/DFAT/offshoreenergytoday.com/GeoscienceAustralia (AFP).

On 9 May 2018, East Timor and Australia signed an historic maritime boundary treaty, finally ending nearly fifty years of wrangling over the vast resources in the Timor Sea. Ratified on 30 August 2019 — the 20th anniversary of the country’s independence referendum — the new treaty now gives East Timor control over the Greater Sunrise fields, valued at about US$40 billion.

Australia’s Prime Minister Scott Morrison and East Timor’s Prime Minister Taur Matan Ruak exchange the ratified maritime boundary treaties. Credits: Premierminister Osttimors, Public domain.

This is a significant victory for one of Asia’s poorest and youngest nations. The former Portuguese colony declared independence in 1975, only to be violently occupied by Indonesia from 1975 to 1999. Administered by the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor from 1999 to 2002, East Timor became independent in May 2002 and held a truth commission to heal from the mass violence that led to the deaths of 200,000 people.

But the nation’s ability to benefit from natural resources in its maritime boundary has been frequently thwarted.

The Timor Sea has been divided through many unequal treaties. Indonesia and Australia signed the first of these in 1972. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), signed ten years later in 1982, states that a maritime boundary between two coastal states should be at the median line. Simply put, it should be at the half-way mark in the sea.

The 1972 treaty put the boundary at the edge of Australia’s continental shelf, which placed most of the oil and gas reserves in the Timor Sea in Australia’s hands. Portugal did not agree to the treaty and that created the Timor Gap — the belt of the Timor Sea adjacent to East Timor.

The question of what would happen to the Timor Gap was resolved when Indonesia invaded East Timor in 1975 and annexed it, calling it the 27th province of Indonesia. The Greater Sunrise fields had already been discovered in 1974. With oil and gas at stake, Australia became the first western government to recognise Indonesia’s occupation of East Timor. Although the rights and freedoms of people are enshrined in Australia’s democratic system, it was politically expedient to resolve permanent seabed boundaries with Indonesia.

Timorese people re-enact the 1991 Santa Cruz massacre that took place in Dili, as an act of protest. Credits: Mark Rhomberg/ETAN, CC BY 4.0.

Dissatisfied with the 1972 agreement, Indonesia renegotiated a new treaty with Australia, which led to the Timor Gap Treaty of 1989. It carved out of a zone of cooperation to share proceeds from the Greater Sunrise deposits. In February 1991, the treaty was ratified. Portugal initiated a lawsuit against Australia at the International Court of Justice because the treaty violated East Timor’s right to self-determination. Unfortunately, nothing came of this and the violence continued, culminating in the massacre of over 250 Timorese by Indonesian troops at Santa Cruz cemetery in Dili on 12 November 1991.

A timeline of all the negotiations and treaties signed between Portugal, Australia, Indonesia and East Timor from 1972 – 2019. Source: Maritime Boundary Office of East Timor.

Following East Timor’s independence in 2002, the Timor Gap Treaty was no longer in force. Australia entered into a series of treaties from 2002 to 2006 with the newly independent country. The 2002 treaty established a Joint Petroleum Development Area (JDPA), with a 90:10 revenue split in favour of East Timor.

Things changed considerably in Australia’s favour with the 2006 treaty. Both countries agreed that the Greater Sunrise Unit Area (GSUA) revenue would be shared 50:50, and that the establishment of an actual maritime boundary would be deferred for another fifty years. At this point, Australia was already drawing from the Bayu-Undan field situated in the Timor Sea and profiting from it. Discovered in 1995, the Bayu-Undan field is within the Joint Petroleum Development Area (JPDA) and was operated by ConocoPhilips Australia, a majority shareholder, until 2018.

People in Brisbane protesting Australia's claim on East Timorese oil. Part of the May Day parade - 1 May 2017. Credits: Andrew Mercer, CC BY 4.0.

The 2006 treaty also became invalid when it emerged that Australia’s secret intelligence service had conducted espionage. They bugged East Timor cabinet offices in 2004 to gain an advantage for the 2006 treaty negotiations. The breach was so significant that East Timor later brought a case concerning Australia’s misconduct to the International Court of Justice.

That ultimately paved the way for East Timor to initiate unprecedented conciliation proceedings under UNCLOS in 2016, leading to the ratification of the 2018 treaty. Australia now owes East Timor billions in compensation for drawing from several oil fields in the Timor Sea, though it is unlikely those payments will be made.

Credits: Alexander Simoes, CC BY 3.0.

East Timor is heavily dependent on petroleum and gas. Over US$20 billion has been funneled from Bayu Undan into the country’s Petroleum Fund.

Yet that field will run out of gas by 2023. All bets are now on developing Greater Sunrise. TimorGap, the country’s state oil company, bought out ConocoPhillips and Royal Dutch Shell to gain a majority ownership of the oil and gas fields. At the heart of this buy-out is the location of the pipeline. Most companies, including another key player Woodside, may vote in favour of piping it to Darwin. East Timor disagrees.

The government wants to develop its human capital and invest in “long-term economic activity”. That means establishing the pipeline in East Timor. For the country’s leaders who fought for independence, having clear land and maritime boundaries and the autonomy to manage its own petroleum industry is a key part of its strategic development plan.

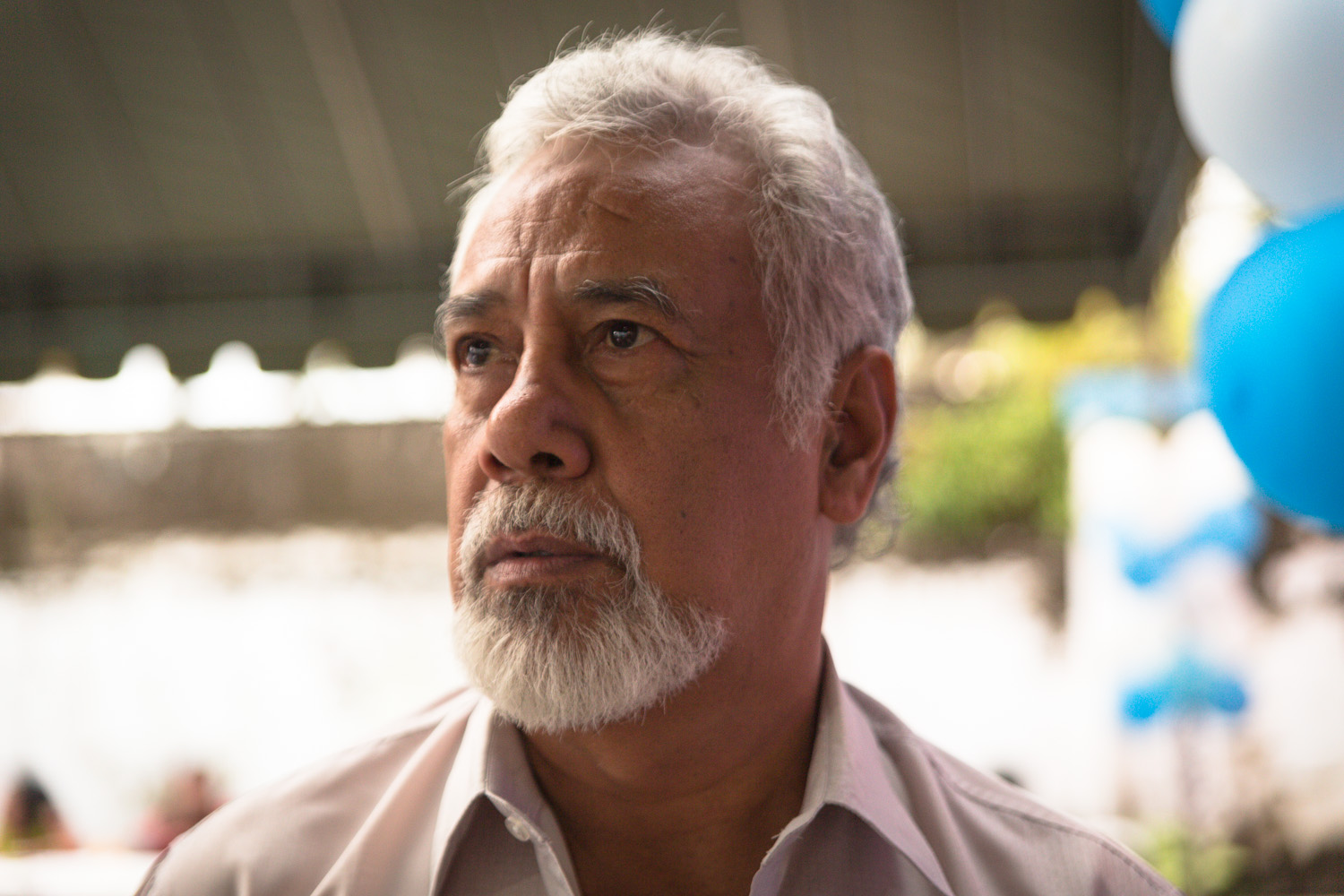

Xanana Gusmao, a key figure in East Timor’s struggle for independence, also served as the country’s president (2002-2007) and prime minister (2007-2015). Credits: Isabel Nolasco, CC BY 4.0.

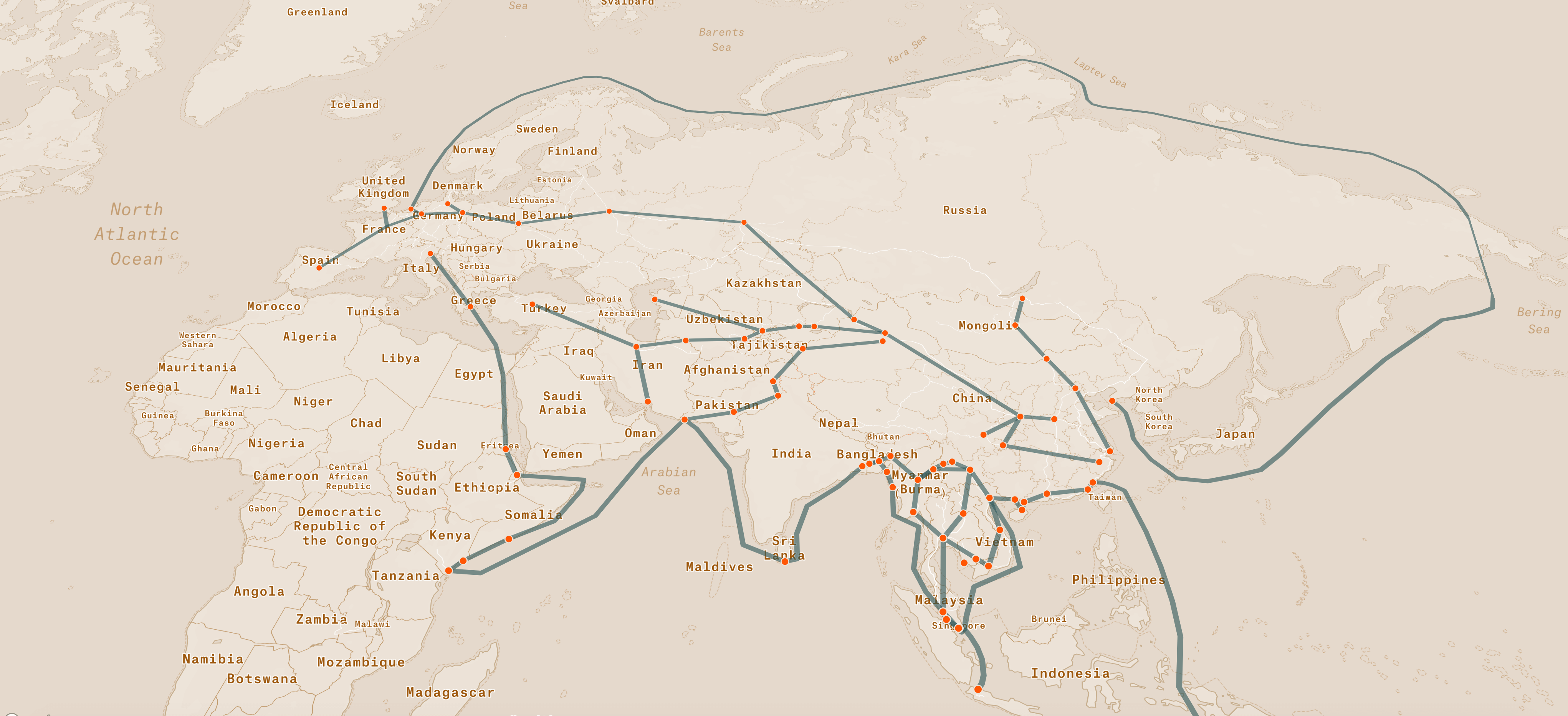

That means East Timor will continue to develop the ambitious Tasi Mane infrastructural project on its southern coast, which is estimated to cost US$15 billion. It is also looking for a new partner to support its plans. That new partner might be China. It has already invested millions towards infrastructure projects in the East Timor, from government buildings to power grids and highways that tie in with its Belt and Road Initiative vision.

While critics may balk at China’s growing influence in the Pacific and Southeast Asia, it is Australia’s influence and resource exploitation of the Timor Sea that East Timor has struggled with for decades. The ratification of the 2018 treaty marks a new chapter for the young nation as it seeks to meet the country’s development needs.

Note: This story was updated on 6 November, 2020, to include the signing date of UNCLOS treaty, as the original article had not noted it.

Vinita was an editor and writer at Kontinentalist. She has previously worked at Wildlife Reserves Singapore and co-founded an NGO to represent survivors of genocide in Cambodia before the Khmer Rouge Tribunal. She enjoys her daughter's animated babbling; swimming in oceans; Hindu mythology; ancient temple ruins; social justice and punk rock.

Kathy used to write marine and environmental stories at Kontinentalist. She was history-trained but does other things now instead, like running an ecotourism shark conservation business, The Dorsal Effect. When free, she enjoys being in the ocean, trying to spot some sharks or just home cuddling with her cavvie, Danea.