Big, bold democracy—India votes

by Vinita Ramani

Close to 900 million Indians are heading to the polls that started on April 11 and will end on May 19 to vote for their next government. A host of issues plague the incumbent Bharatiya Janata Party, from rising unemployment in urban India, to plunging crop prices hurting its rural population. What will the people decide and why should India’s political parties pay attention to the 84 million first-time voters?

Watching the world’s biggest democracy go to the polls can be mind-boggling. The 2019 Indian elections is the world’s largest and also the most expensive. Indians from 29 states and seven territories can choose from more than 2,000 political parties. Over 1 million polling stations have been set up to facilitate the process. From goats for votes, to chicken curry, television sets, and alcohol, candidates across the country will try just about anything to win favour with the people. At its conclusion, Indians will have decided which party or coalition has a majority in the Indian Parliament’s Lok Sabha, or the lower house. That winning coalition will choose India’s next Prime Minister.

Politics in India can be mired in corruption and political grandstanding, with worries about the criminalisation of politics. But for the 84 million new voters, nearly 18 percent of which are 18-19 year olds, tolerance, secularism, and sustainable living are also critical for the future of India. So who will India’s electorate hedge their bets on?

The big players in India's election

India’s diversity makes it more like a union of nations than one nation. Neither the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), nor the Indian National Congress (INC), can go it alone. They have to form alliances with other political parties to be in power. A political party has to be recognised in at least four states and generally have a ‘pan-Indian’ presence to qualify as a national party. In India, there are five national parties beyond the BJP and INC. There are also 35 state-level parties and hundreds of regional parties which meet the needs of communities at the most localised level. They represent ideologies right across the political spectrum, from communism, socialism, right-wing religious nationalism, to democratic socialism and secularism.

Parties tend to fragment as personalities clash and politics diverge. Many national parties are breakaways from the Indian National Congress.

Knowing that you are only as strong as your alliances, the BJP created the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) in 1998 to consolidate centre-right and right-wing parties. INC followed suit, and created the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) in 2004 to bring left and centre-left parties together. This is how the alliances work in theory. Yet, the ground can shift radically and neither Rahul Gandhi, nor Narendra Modi, can afford to ignore those changes, or their own party’s failings.

Results from 2009 to 2014 show how the BJP wrested much of the nation from the INC, while strong state parties retained control on home ground.

In 2009, INC together with an array of parties under the UPA won the elections, garnering 262 seats in the Lok Sabha. Additional support came from several parties, allowing them to make up the shortfall and bolster its presence in parliament. INC’s handling of the economy, its pro-poor policies and the people’s vote for political stability ensured victory. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh was elected to a second term in office. Nobody since India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru had served two terms.

But the celebrations ended there. From 2009 to 2014, the party’s reputation was mired by a series of corruption scandals, debt, poor leadership, and dissension within the party.

By 2014, Indians were ready for change and the tide turned dramatically. The party suffered a massive defeat as the BJP swept into power, grabbing a clear majority in the Lok Sabha with 282 of the seats. It was an election of dramatic firsts: other than the INC, no party had ever obtained a majority of the seats before. INC had never lost so humiliatingly, with just 44 seats.

The INC and their allies won the elections in 2009, with 48% of the seats in parliament and support from external parties. But in 2014 the BJP and their allies won by an overwhelming majority, with over 60% of the seats.

Social media statistics for the two main parties, as well as Modi and Gandhi, show that Modi has a massive following.

How did a 68-year old former Chief Minister from the state of Gujarat win over the masses in the 2014 election? Much of the BJP’s victory is the story of the power of social media. There are over 500 million Internet users in India and 250 million active social media users. More than half of its 1.3 billion people are under the age of 26 and by 2020, India will be the youngest country in the world.

The party’s IT division foresaw that the best way to reach the youth of India was through online campaigns, an active social media presence and crowdsourcing for ideas. The BJP platform, india272.com (272 being 50% of the seats in the Lok Sabha) tapped on volunteers to “collaborate, contribute and campaign”, giving young voters in particular, a stake in the future of the country.

But it wasn’t just the party’s efforts that paid off in 2014. Active on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, Modi was dubbed India’s “social media prime minister” when the BJP won in 2014. The 48-year old Rahul Gandhi and his Party, in contrast, did not use social media as effectively, and had to contend with a jaded electorate.

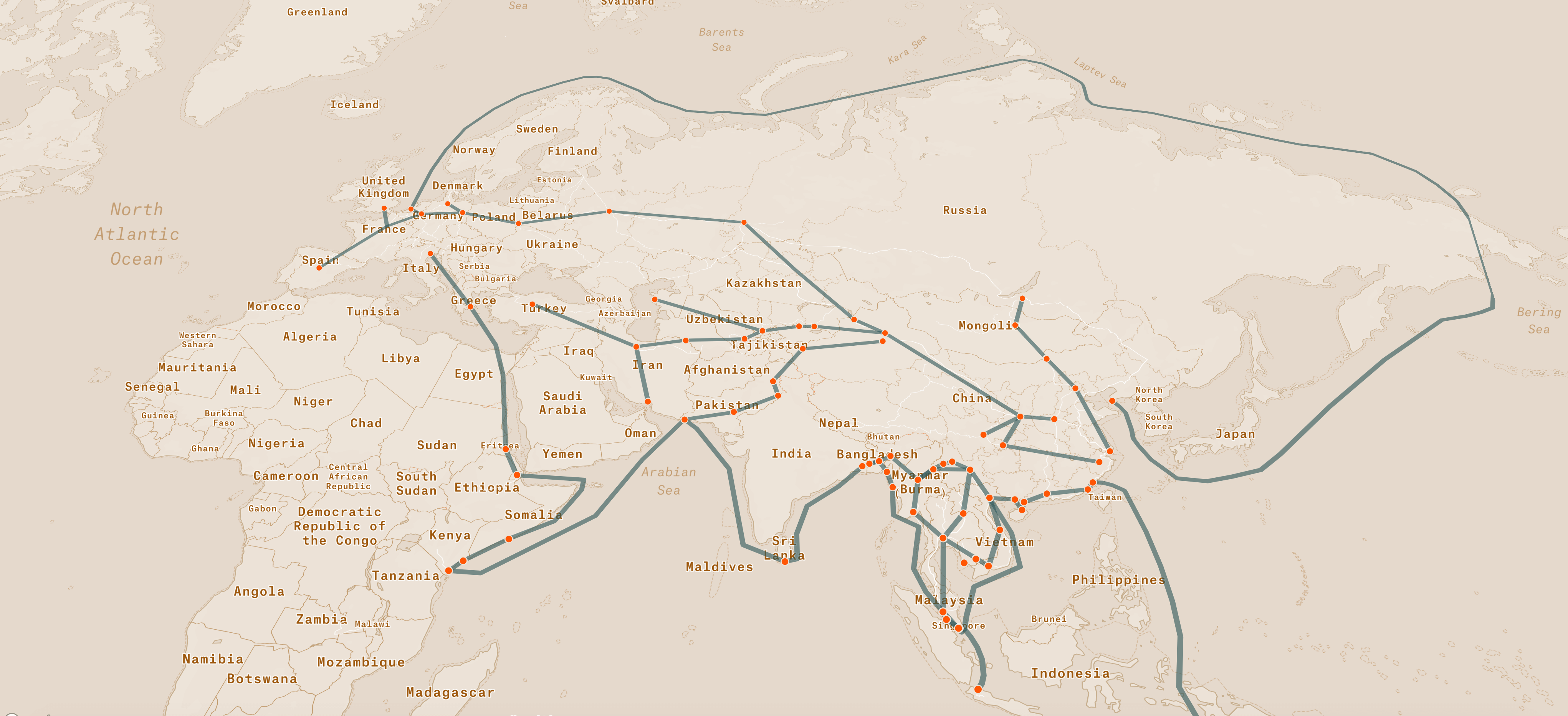

Modi and BJP still appear to be the popular choice in India. For a start, the government’s Hindu nationalist rhetoric has been aided by significant border tensions with both China and Pakistan in recent years.

In mid-2017, Chinese and Indian troops squared off for 73 days in the Himalayas, in an incident that came to be known as the Doklam standoff. India came in swift aid of its ally, Bhutan, when China extended a road into the Doklam Plateau in that country. Military presence and exercises intensified during the period. China and India eventually chose to disengage by end August 2017. India’s approach was globally lauded.

A map of Kashmir

In early February 2019, a convoy of vehicles with over 40 Indian security personnel was attacked in Pulwama district, in Indian-administered Jammu-Kashmir. All the officers were killed and the incident led to an intensification of tensions between the two countries, with airstrikes across the Line of Control (the military control line separating Indian and Pakistani administered areas of Jammu and Kashmir) culminating in a dogfight between Indian and Pakistani jets. In end February, Indian pilot Abhinandan Varthaman, was captured when his aircraft was shot down. After 60 days of captivity, he was released by Pakistan’s prime minister Imran Khan in a gesture of peace.

Both incidents stoked nationalist sentiments in India, and Modi further politicized the Pulwama attack, even if Varthaman himself took pains to state that the Pakistani military treated him well.

Opinion poll trends show that Modi’s popularity is on the decline.

The latest opinion polls also suggest that Modi’s popularity has declined in the past two years. No amount of ‘likes’ on social media, or flattering biopics timed to be released during election season can compensate for practical woes on the ground. The party itself suffered significant defeats in state elections in December 2018, losing the three major states of Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Chattisgarh, considered to be India’s Hindi heartland and traditional BJP strongholds. Adding to this, Gandhi has upped his game on social media, with greater engagement on platforms like Twitter.

Modi came into power under using the moniker “chowkidar” (watchman or gatekeeper) in the 2014 elections, promising that he would not allow any corruption to fester and grow. And he guaranteed jobs for Indians. Rahul Gandhi has shot back in 2019 with a new slogan: “chowkidar chor hai” (Hindi for “the watchman is a thief.”). What has been stolen and why are Indians frustrated?

Infographic on battleground issues in India

Some of Modi’s biggest successes include the creation of “Brand India”, an initiative launched in 2014 to promote India as the destination of choice for businesses in various sectors, as well as significant improvements to infrastructure and development. But many promises have not yet been adequately fulfilled. What are the biggest woes for the electorate? Four key areas capture what Indians are struggling with:

In November 2016, Modi made a shock announcement that all 500 and 1000 rupee notes would be removed from circulation, in a move to flush out untaxed wealth. The move sent millions of Indians scrambling to exchange their demonetised currency to usable bank notes. The policy hit farmers, SMEs, and lower-income households the most severely. In sum, it hit India’s large, informal economy. There was a corresponding spike in unemployment in 2017 and 2018 following the crisis.

Despite being the fastest growing economy in the world, unemployment surged to 6.1 percent in 2017 to 2018 — a 45-year high. The two segments of the country worst hit by this are India’s Generation Z and the rural population. Young, urban Indians are struggling to find jobs. Familiar statistics continue to circulate about India: 20 million Indians applied for 100,000 job openings at the Indian railways. Various sectors continue to point to demonetisation and India’s introduction of a goods and services tax as the reasons for rising unemployment.

The rural population of India represents over 66 percent of the country and they are lagging behind with declining wage growth. Farmers are also being hit by several BJP policies, in addition to the effects of demonetisation. The government, echoing its conservative Hindu stance, shut down unlicensed abattoirs and slowed the trade in cattle because cows are considered sacred by Hindus. That move has hit Muslims in India and even Hindu farmers, who have lost the money they would have earned, selling unproductive cows to Muslim traders. Meanwhile, little has been done to rehabilitate the animals. That, coupled with depressed earnings, rising costs of fertilisers and diesel, have left India’s farmer feeling disenfranchised.

Despite his popularity with youth voters and his many contributions to improving India in the past five years, Modi and the BJP party still promote a rhetoric that favours a religious, conservative vision of India. The party’s decision to appoint the right-wing Yogi Adityanath the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh in 2017 has left the region’s minorities nervous. It has also had the effect of bolstering some of India’s most powerful national and state parties, who question and challenge the BJP’s right-wing Hindu ideology.

Key state/national players in the 2019 Indian Elections

The smaller national and state parties of India may not have the clout to win by a majority like the BJP, or have a prime ministerial candidate in their midst. But there are charismatic politicians who challenge the ethos of both the BJP and INC.

Uttar Pradesh is the largest state in the country and therefore occupies 80 seats in the Lok Sabha. In this state, two former rivals have become allies to give the BJP a run for its money. The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) is led by the charismatic 63-year old Dalit leader Mayawati and the state-level Samajwadi Party (SP) is led by 40-year old Akhilesh Yadav. Even if controversy surrounds Mayawati, she is well-loved. Both politicians have been chief ministers of the state and focus on social change for the bahujans—Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, religious minorities and Other Backward Classes.

In West Bengal, Mamata Banerjee is a force to be reckoned with. She started her own party, the All India Trinamool Congress in 1998 and in 2011, her party won the elections, ousting the Communist Party of India (Marxist), which had been in power in West Bengal for over thirty years.

In the south of India, the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) entirely dominate the state of Tamil Nadu, led by its chief minister Edappadi K. Palaniswami. K. Chandrashekar Rao is the face of Telangana, the new state that was carved out of the southern state of Andhra Pradesh in 2014. He heads the Telangana Rashtra Samiti (TRS) and is the new state’s chief minister. He has avoided an alliance with either the BJP or the INC and has the ability to have considerable political influence in the Lok Sabha and the state itself.

There are many Indias. Statistics on unemployment, poverty, literacy, crime and gender equity further divide the country. Kerala has a literacy rate over 90 per cent, while Bihar’s is just above 60 percent. Tamil Nadu has risen economically, while Uttar Pradesh is still languishing. India continues to experience uneven growth. Tackling such wildly different needs in a nation of over 1.3 billion people is no mean feat. What remains to be seen is which party, through what alliance, can mend the woes of India today.

Loki.ai provides end-to-end data solutions for content creators. Loki’s proprietary technology helps creators acquire, analyze, and visualize data automatically. The company serves some of the biggest media companies, think tanks, and government agencies in Asia – including the Times of India, NUS Institute of South Asia Studies, and the Singapore Ministry of Foreign Affairs.