China and the US

Who will win the battle for dominance in the Pacific?

by Han Shih LeeAfter Huawei and soybean, US and China are gearing up for the next battle—a land grab in West and South Pacific. What lies ahead for the Pacific Island countries and how will this change the geopolitical balance in the region?

From space, the islands dotted over the world’s biggest ocean look like thousands of sesame seeds floating in a giant bowl of blue-green punch. There is hardly any land to speak of.

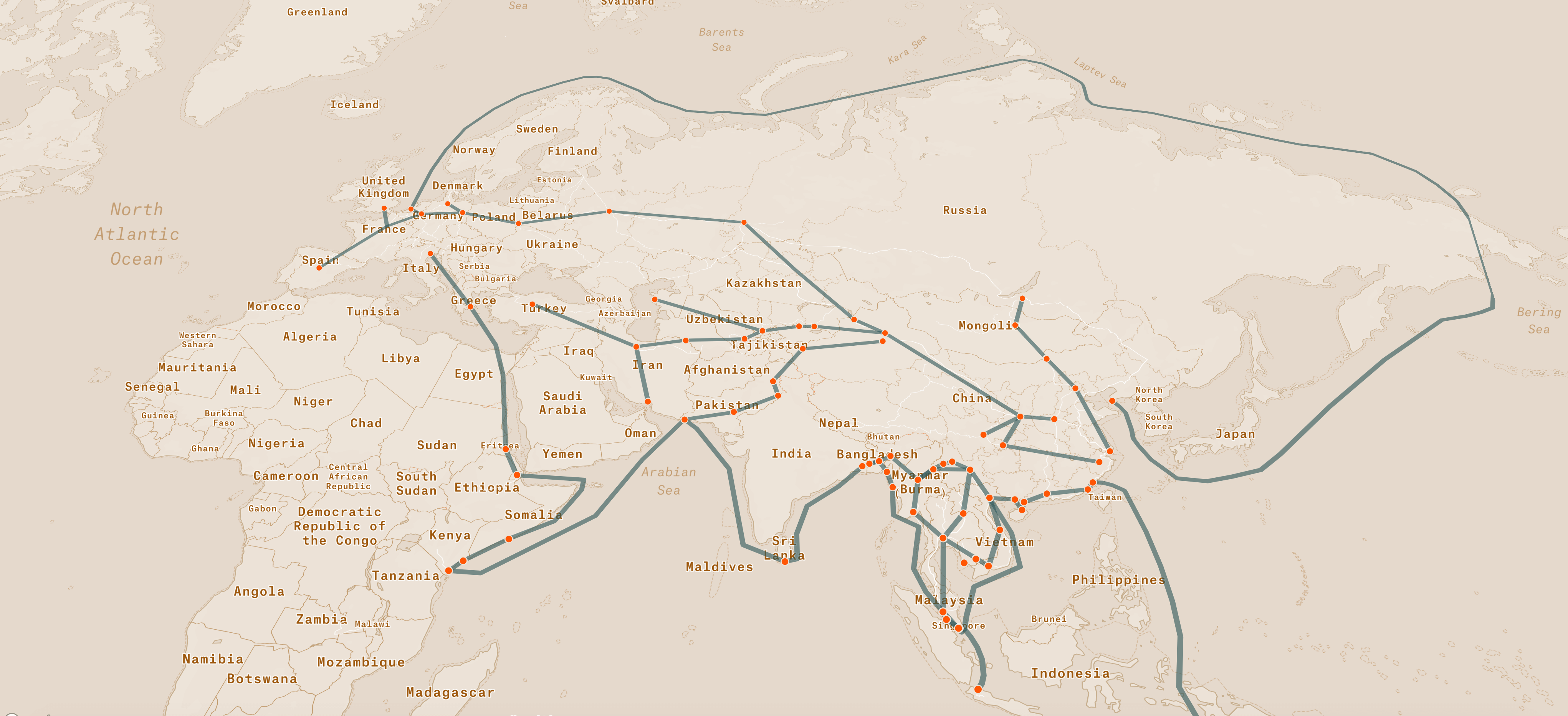

But that does not stop the US and China from fighting for vassal states. The US already has a clutch of them, from Guam to Samoa. China is trying to pry some from Uncle Sam. Since President Xi took office in 2013, China’s presence in the region has only increased. Recently, official Chinese government statements and policy documents have included the Pacific Islands as part of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Interactive map of the Pacific Islands.

These islands are grouped into Polynesia (‘many islands’, central and south Pacific), Micronesia (‘small islands’, west Pacific) and Melanesia (‘islands of black people’, southwest Pacific). The three biggest—Australia, Papua New Guinea and New Zealand—are not openly involved in the US-China dispute.

The rest are tiny: the Solomon Islands (1,000 islands totalling 30,000 sq km), Fiji (20,000 sq km), Vanuatu (12,000 sq km), Samoa (2,800 sq km), all the way down to islets visible only at low tide.

Some sixty years ago, the islands were used by the US and France for nuclear testing, being conveniently located far from their home countries. No consideration was given to the inhabitants of these islands. Little has been done by the US to resolve the lasting environmental degradation, negative health outcomes, and distrust caused by the nuclear testing program.

Today, the geopolitical locations of the Pacific Islands again come into play. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) gives these islands varying degrees of sovereignty hundreds of kilometres from their coastlines. Collectively, the area of the Pacific Island countries comes to about 552,000 square kilometres and has a population that is just over 10 million. But they ‘control’ almost 20 million square kilometres of ocean.

An interactive map of the Free Trade Zones.

The US dominates the Pacific courtesy of its ownership of Guam and other islands, and through its Compact of Free Association (COFA) with the Marshall Islands, the Federated Republic of Micronesia, and Palau.

Under COFA, the US bestows money and certain benefits to citizens of the three countries, such as the ‘right’ to serve in the US army. In return, it directs their foreign affairs, while its Pacific Fleet—200 ships, submarines, and aircraft carriers, 1,200 planes and 130,000 sailors—has free run of the ocean.

COFA needs to be renewed at the latest by 2023. The US is concerned the Pacific nations may ‘defect’ to China, which is spending billions there, likely looking to set up military bases. Taiwan is also a key U.S. partner in the Indo-Pacific. Six of the 11 nations have diplomatic ties with Taipei but Beijing is pushing for them to switch recognition. If COFA changes hands, China will gain control of the waters and (theoretically) the right to deny passage to US warships. It would also shrink Taiwan’s international airspace.

The US may think COFA is only a matter of money. But the priority of the Pacific nations is survival—global warming is rising sea levels rapidly and many islands are just one to two metres above the water. In 2015, they persuaded the Paris Agreement state parties to limit global temperature rise. Eighteen months later, Donald Trump pulled the US out of the agreement.

With the threat of sea level rise, China’s proven ability to build new islands in the South China Sea, or raise the levels of existing ones may offer a solution to the Pacific nations. But island-building could mean increased militarization in disputed waters, or areas of strategic importance.

If money is the issue, China can solve it. Its loans come with concessional interests and must eventually be paid back. Some Pacific Islands have asked for the loans to be written off, which raises questions on how small economies can manage their debt burden. Despite these issues, a second term for Trump and ongoing climate change denial could push the Pacific nations into the arms of China.