Panda diplomacy

Gifting pandas to further China’s politics

by Naomi Clark-ShenThroughout history, China has gifted giant pandas to other countries to foster better ties. Known as animal diplomacy, this act of soft power—no pun intended—can showcase goodwill, create a commitment to reciprocity, and signal hierarchy. So, which nations are China bonded with, and what does this suggest about their relationship?

While culture, language, and politics create barriers between people and nations, animals have the ability to bring them together: they create awe and make us go “awww” regardless of their nationality. This is likely the reason why, for centuries, the leaders of many nations have gifted animals to forge alliances—such as when establishing diplomatic ties and partnerships around trade. The species gifted are usually exotic, iconic to the gifting country, and not found in the recipient country.

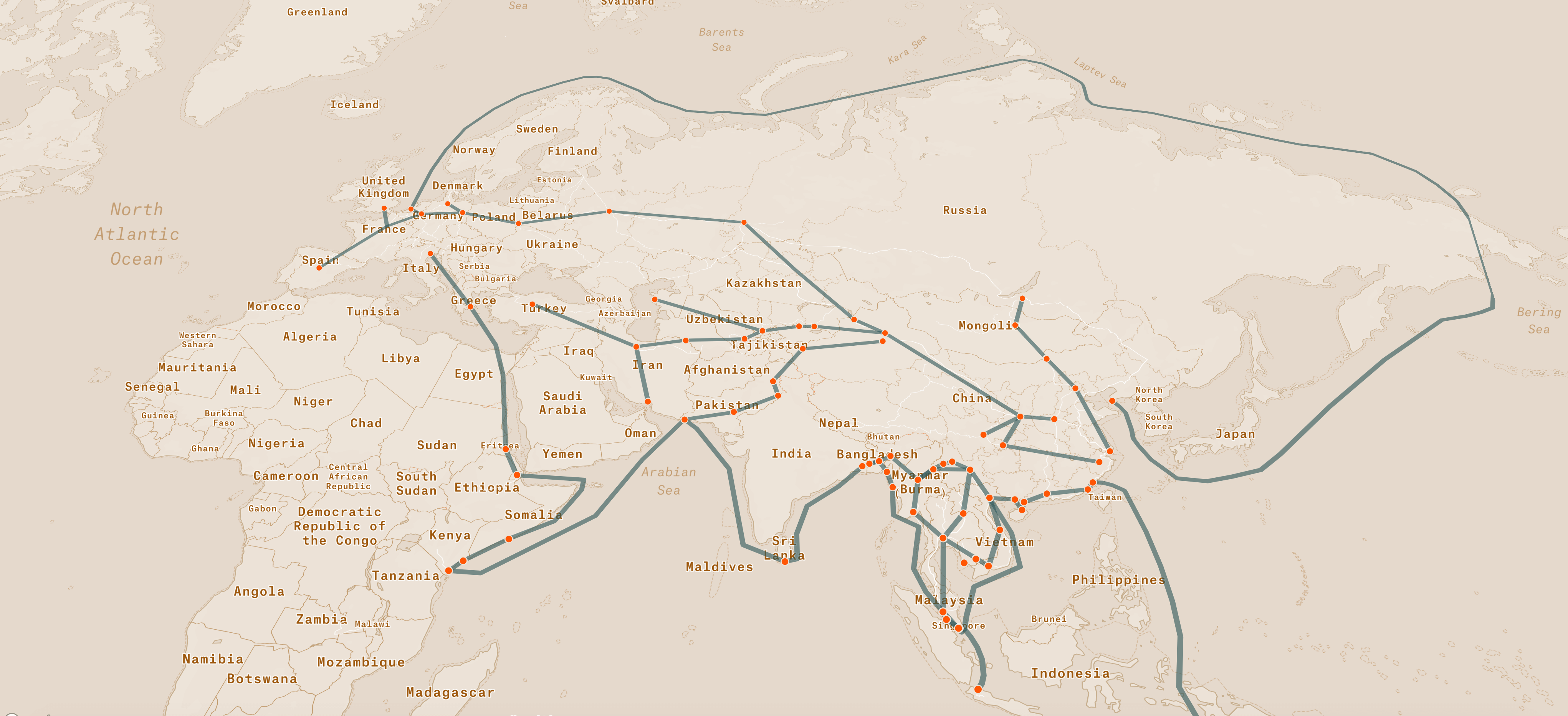

Explore the map for some examples of animals gifted between countries.

Giant pandas are only found in China; they are very rare, and are even scientifically proven to have outrageously cute features. They are, essentially, the perfect secret weapon for China to woo other countries with, helping them appear soft and friendly as they rise as a world superpower. This may come as no surprise, considering that gift-giving in general is considered good etiquette in China and other parts of Asia; in many of these cultures, gifts communicate respect, hospitality, and friendship.

China has been gifting pandas since the Tang Dynasty 1,300 years ago. But in the 1990s, the government decided that it would no longer give its pandas away but loan them out instead. These panda loans typically last ten years at a cost of US$1 million per year, and establishments must also bear the cost of food and general upkeep. The expense is worth it, however, because of the resulting ‘pandamonium’—causing visitor numbers and revenues for some zoos to surge.

The switch from gifting pandas to loaning them has not made panda diplomacy any less prestigious, and recipients are still strategically selected. In recent years, many of these loans have coincided with major trade deals between China and recipient countries—from uranium, to food and healthcare. Other loans have been interpreted as power plays, such as when China gifted giant pandas to Hong Kong and Taiwan, both Chinese territories with strained relationships with the mainland.

Today, there are over 50 giant pandas in more than 20 countries and territories outside mainland China.

Explore the map to see which countries have giant pandas from China—and why.

Giant pandas symbolise not only relationships that are strengthening—but also relationships that are breaking down. Giant panda loans and gifts that have gone wrong highlight diplomatic ties that are fragile.

In 2019, when the giant pandas at the San Diego Zoo were returned to China, there was speculation that it was because of the ongoing US-China trade war. However, zoo officials maintain that the panda programme at the zoo had reached its planned end after 23 years, and not because China had recalled its animals.

Animal rights groups have condemned the cruel methods used to breed giant pandas, which are loaned to other countries as part of a ‘captive breeding programme’. When natural copulation fails, males are electro-ejaculated and females artificially inseminated. Any panda cubs born overseas are returned to China after a few years to continue the breeding programme.

The captive breeding programme is portrayed as a conservation effort, to boost the numbers of these endangered animals—there are fewer than 2,000 giant pandas left in the wild. But scientists argue that the increase in captive-born giant pandas has not translated into real world conservation. Despite hundreds of births in captivity, only a few giant pandas have reportedly been released into the wild, to mixed success.

Animals raised in captivity generally lack the skills to survive in the wild, especially because many have been raised by human care-takers. As a result, the captive population has increased considerably compared to the wild population. While this has progressed China’s diplomatic relationships, it appears to have done little for the status of endangered pandas in the wild.

China is now better preparing its captive giant pandas for release into the wild. Contact between humans and pandas is being restricted, and pandas are being placed in more challenging environments to prepare them for challenges in the wild. But experts believe that efforts should focus instead on preserving and improving the giant pandas’ natural habitats if current and future populations are to even survive in the wild. Habitat loss and fragmentation by dams, roads, and mining have left giant panda populations isolated, with little space to themselves. Reportedly, 70 percent of the US$1 million panda loan fee that countries pay annually goes to the conservation of giant pandas in China, but it is unclear how this money is spent.

There is no doubt that China, as well as the world, values giant pandas. These endangered animals were chosen for the logo for the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) as a “strong, recognizable symbol that would overcome all language barriers.” China even enforces a hefty penalty for killing their national treasure: a minimum of ten years in jail and, in severe cases, a life sentence or the death penalty.