BirdLife International is a global partnership of 115 conservation organisations (NGOs) that strives to conserve birds, their habitats and global biodiversity, working with people towards sustainability in the use of natural resources. BirdLife Partners, which are independent environmental or wildlife not-for-profit, non-governmental organisation (NGO), work together in a collaborative, coordinated fashion across national boundaries to build a global Partnership of national conservation organisations.

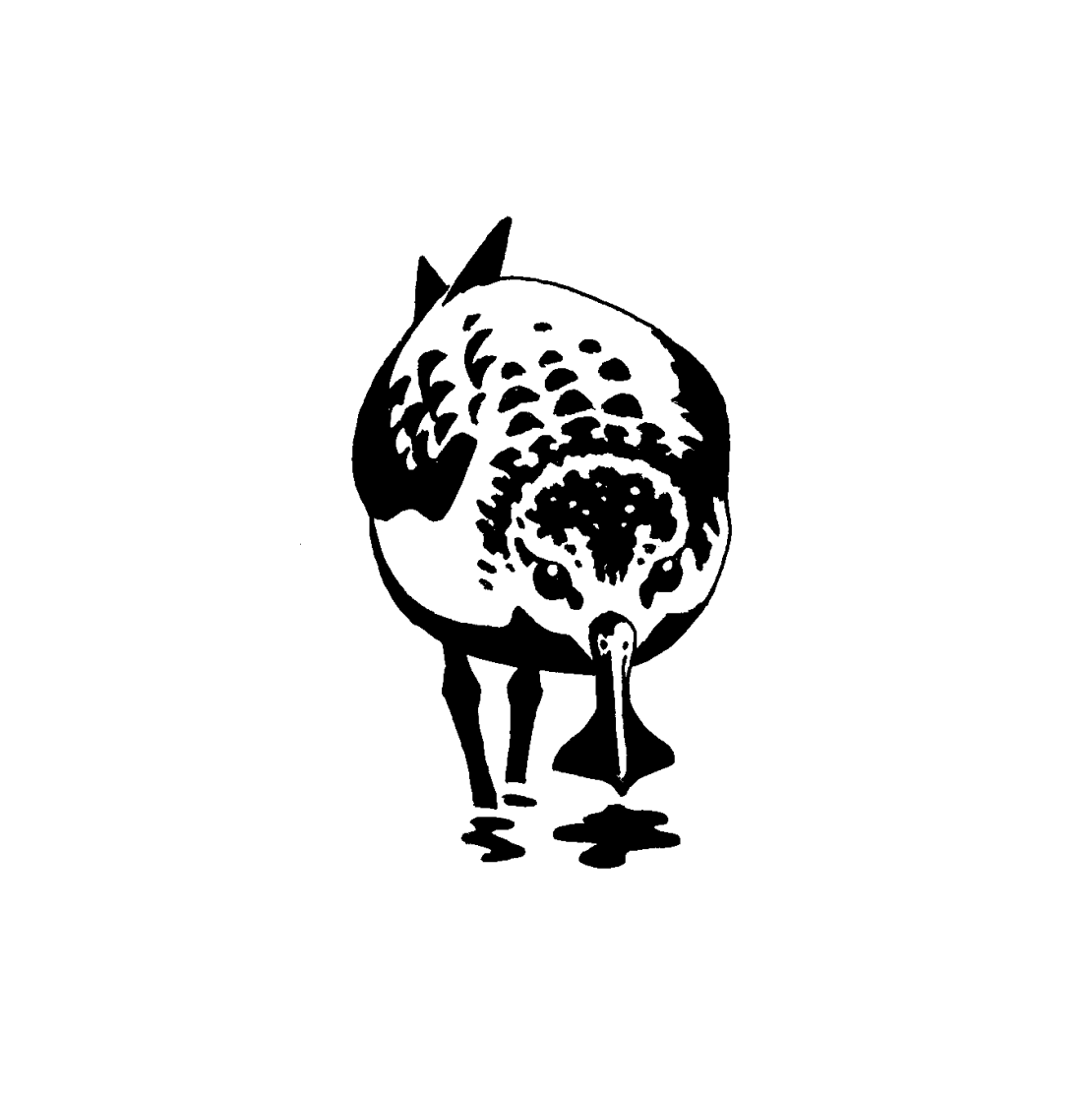

In 2004, several organisations active in the conservation of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper joined the Spoon-billed Sandpiper Recovery Team (SBS RT). In 2010, the SBS RT joined the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership (EAAFP) and was officially established as a species Task Force (Spoon-billed Sandpiper Task Force). The task force works to coordinate the conservation activities identified under the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) Single Species Action Plan for the species commissioned by BirdLife International and is regularly updated in consultation with leading experts worldwide.