The power of pragmatism

China’s belt and road to the Islamic world

by Pei Ying LohChina’s Belt and Road Initiative has been shaking things up all across the world. Among the countries who have registered interest in the initiative are those with large or predominantly Muslim populations. In recent months, China’s relationship with some of these countries have piqued interests and started debates. What exactly is happening?

The Islamic World is more than a geographical reference. It is a concept that refers to both historical and geographical imaginations where the Islamic faith plays a significant role. This spans regions and societies that are heavily influenced by Islamic qualities because Muslims form the majority, or have a significant presence.

When we think of Islam, naturally we think of the Middle East where the religion originates. Yet, our imagination of the Islamic world rarely stretches beyond those borders. In reality, large parts of North Africa, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia are predominantly Muslim.

Our modern understanding of China and the Islamic world, is that they are distinctly different and detached entities that have no shared history. That is not true.

China’s connection with the Islamic World is one that dates to antiquity, largely thanks to the silk routes. Islam’s presence in China is as old as the religion itself—it is said that sahaba (companions) of Prophet Muhammad had travelled to the country and introduced the religion during the mid-7th century. Likewise, “blue and white porcelain”—one of the highest art forms of Chinese culture—has its roots in Islamic culture. The cobalt blue pigment crucial to these pottery forms were imported from Persia, and was popularised first in Islamic pottery under the Abbasid Caliphate.

In more recent times, China’s dealings with Muslim-majority countries are largely grounded in pragmatism. Following the leadership of Deng Xiaoping from the 1970s and the end of the Cold War, China’s foreign policy towards these countries is based on practicality and economic prudence. While it has diplomatic ties with these countries, it remains distant. This is especially so with the Middle East where China describes itself as a “bystander”. Its affinity with these countries start and ends with economic sensibilities, and a big part of that is oil.

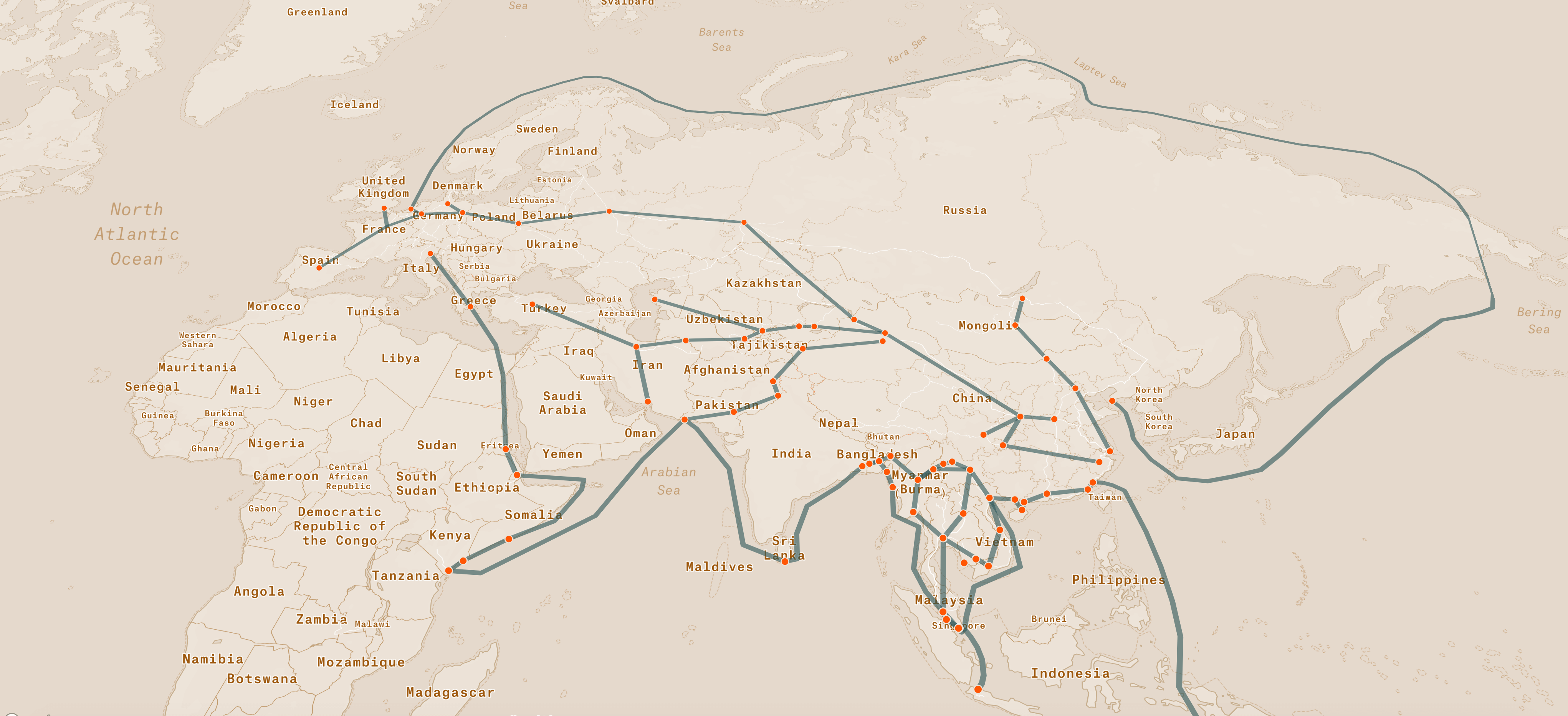

In 2013, President Xi Jinping introduced the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to the world. The BRI outlines China’s grand ambition to connect countries across three continents through the revival of historic silk routes. Obviously, these routes go through Central Asia, Middle East, North Africa, and Southeast Asia—all of which are regions where Muslims form a majority or have significant presence.

Countries selected and shown here have a more than 50 percent population of Muslims.

This initiative is all about building railways, roads, airports, and so on. For it to take off, it requires the long-term involvement and commitment of these countries. China understands this, and since the inception of the BRI has been working hard to cultivate relationships with these nations.

In the early years of the BRI, China only made a handful of agreements with Muslim-majority countries. However since 2017, this has been significantly accelerated, and now it has made bilateral agreements or partnerships with around 45 Muslim-majority nations. China has been careful to call these diplomatic relations ‘partnerships’ as opposed to categorising the countries as ‘allies’—a continuation of its ‘bystander’ policy.

China has made significant show that these regions matter. In 2018, at an Arab summit in Beijing, President Xi Jinping pledged US$20 billion in loans, and another US$106 million in financial aid to the Middle East. It also later offered US$60 billion to Africa to aid development.

China’s investments in the Islamic world is consistent with its behaviour elsewhere. The bulk of it is in the energy and transport sector, which is no surprise. The Islamic world is rich in energy resources, and the Middle East and North Africa is a crucial land bridge connecting China to Europe. More interestingly but of lesser weight, China has also been providing quite a bit of assistance towards emergency response, food and non-food aid, sanitation, education, and other social infrastructure.

China-related projects in Muslim-majority countries.

On a whole, the bulk of the Islamic world has signalled that it welcomes China’s investment and cooperation. Iran for one, has been an eager partner to the BRI. Due to sanctions pushed by the US, China opens a big market for Iran. One of the key projects is the Tehran-Mashdad Electric Rail, which is being co-funded by the EXIM Bank of China. Saudi Arabia has also sealed deals with China worth billions, and will include plans for a refining and petrochemical complex. Just this April, the United Arab Emirates has announced a US$3.4 billion deal with China to build a ‘Traders’ Market’ that will include cold storage warehouses. Chinese companies are also building a new administrative capital in Egypt, and China’s COSCO Shipping Ports has a 20 percent stake in Port Said at the Suez. These are just some of the near hundreds of projects covering ports, industrial parks, rail lines, energy plants, and so on that China and its companies are involved in across the Islamic world.

China has also been making efforts towards facilitating Islamic finance. Islamic finance refers to the manner in which Muslim countries raise capital in financial institutions in accordance with Sharia or Islamic law. In 2018, the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Islamic Development Bank—a multilateral bank that focuses on Islamic finance—to jointly finance projects in Africa and other developing countries. The AIIB is purportedly considering using Hong Kong as a sukuk—an Islamic financial certificate—issuance base. Banks like the Industrial Commercial Bank of China, and the Qatar National Bank, have also made efforts to make access to and investment in Islamic finance easier.

It will be difficult for China to navigate this terrain. While the term “Islamic world” suggests that these Muslim-majority areas are a monolithic group, they are in reality incredibly diverse. Shia and Sunni Muslims have differing practices and interpretations of the faith. In some instances, this becomes a divisive line among Muslims. There are also political power tussles, with Saudi Arabia and Iran vying for leadership of the Islamic world. If all of this is not enough to contend with, over 200 languages are used across the Islamic world. The sheer linguistic diversity poses a difficult challenge to any country seeking inroads. There is no one-size-fits-all strategy.

Fortunately for China, real politics runs strong in the Islamic world as well. The desire to resist American influence works in China’s favour, and the BRI is an effective bandwagon for this. In vein with, “my enemy’s enemy is my friend”, China also has a historically close relationship with Pakistan, with both countries aligned against India. This took root when India and China went to war over disputed borders. Now, India is also one of the loudest opponents of the BRI, and Pakistan plays a key role in one of the planned corridors.

Stability will also be a challenge for China. Many Belt and Road projects are infrastructure heavy, and are for the long haul, taking decades to complete. China is also the world’s largest crude petroleum importer, and Muslim-majority countries provide nearly 45 percent of the world’s supply. Regime change and transfers of power can be a problem. For example, Malaysia has shown that a new government can easily dismantle plans, although things appear back on track for now. This will be even more trying in the Middle East, where war and conflict has almost been a constant for the past half century.

China understands that stability is important to protect its interests, especially near areas where they have economic corridors planned. For example, it has made engagement efforts with the Taliban in Afghanistan and promoting peace is likely to ensure the success of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor. It has also contributed aid to war-torn Syria, and signed three agreements with the Syrian government to continue providing humanitarian aid. It has also pledged financial support to Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, Yemen, and Libya.

Islam is not foreign to China due to the religion’s long presence in the country. Five out of 14 of China’s neighbours are Muslim-majority countries. China’s borders with these countries have been fairly permeable historically, creating pockets of Muslim communities within the country.

China has 55 recognised minority nationalities, of which ten are muslims. These ten groups are all distinctly different from each other, with different identities, histories, and languages. The largest group of the ten are the Hui, and they are also the only group that is geographically dispersed throughout China. The rest are predominantly located in northwest China, and they are the Uighur, Kazak, Dongxiang, Kirghiz, Salar, Tajik, Uzbek, Bonan, and Tatar.

The diversity of muslims in China has been both a help and a hindrance. China has sometimes used its harmonious relationship with some of these groups, namely with the Hui, to promote a positive image of itself, and convince foreign nations of its respect for Islam. For example, the country boasted in 2017 of their commitment to support over 12,000 pilgrims on the Hajj.

But one of the greatest challenges for China have been the Uighur, the second largest group of muslims in China. Their home is in Xinjiang, a historic region that was integral to the ancient silk road, and also a crucial puzzle piece to the BRI. It is abundant in natural resources. Xinjiang was annexed and occupied by the Qing dynasty in the mid-18th century, and this historical fact has bearings on modern imaginations of Uighur identity.

Map of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

At different points in time, there have been Uighurs that tried for separatism and almost succeeded. There was the First East Turkestan Republic that lasted from 1933 to 1934, and later the Soviet-backed Second East Turkestan Republic from 1944 to 1949. This has undoubtedly led to a lot of anxiety on both sides. Today, China’s relationship with the Uighurs is a great point of interest to the international community, as China tries to build momentum for the BRI. Given Xinjiang’s importance to the BRI and the tension with the Uighurs, China has kept Xinjiang under tight control. There have been allegations of mistreatment of the Uighurs, to the extent that the United Nations and several others have also raised concerns, especially about the establishment of ‘re-education’ camps.

There are not many that speak for the Uighurs. While the United Nations, Human Rights Watch, and major newspapers have spotlighted their predicament, many expect leading Muslim countries to speak up, or apply pressure on China.

Saudi’s Crown Prince, Mohammed Bin Salman, visited China in February 2019. About $28 billion worth of contracts were signed. Many hoped that he would comment on the issue, despite Saudi Arabia’s history of being silent on this. While he did speak, it was not the outcome they wanted, as he defended Beijing’s actions.

Turkey has historically been one of the Uighurs’ strongest defenders, due to a shared ethnic past. In that same month, the spokesman for its foreign ministry described China’s treatment of the Uighurs as a “great shame for humanity”. China retaliated by closing a Chinese consulate in Turkey, and the ambassador warned that such criticisms will hurt the economic relations between the two countries.

This turn of events shows the financial flex of China. While China needs the participation of the Islamic world for the success of the BRI, the relationship is not equal, and heavily favours China. Iran is a good example of this. China is its largest trading partner at about 30 percent of its trade balance. Yet, it does not even make up one percent of China’s trade.

The same imbalance applies throughout the Islamic world. China has the greater financial might in each scenario.

In January, China hosted officials from the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) on a 10-day tour of Xinjiang. China has openly invited foreign members to visit the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and see for itself if it has been mistreating its Uighur citizens. Just a month before, the OIC—which calls itself the “collective voice of the Muslim world”—expressed concern over the Uighurs in Xinjiang.

All of this culminated in March, when the OIC commended “the efforts of the People's Republic of China in providing care to its Muslim citizens.” It seems like members of the OIC heeded China’s warning.

The Uighur issue may be quelled for now at the diplomatic front. However, this does not stop the media and human rights activists from talking about it. China has to come to terms with the fact that its relationship with Muslims in its own territory will continue to be debated globally.

While the BRI has often been compared to the Marshall Plan, China does not seek to materially alter political systems in participating countries. Continuing its ‘bystander’ policy, it still prefers non-interference, non-alignment, no political influence, and a soft military footprint.

But as it grows increasingly reliant on its Muslim partners and neighbours, be it for trade, commodity, or infrastructure, it will find it difficult for China to disentangle itself from security concerns. As a result, it is unrealistic to remain a ‘bystander’ to the political shifts in the Islamic world as the BRI continues to roll out. If China seeks to replace the United States as a global power, it will have to contend with taking on its pains and responsibilities as well.