Troubled waters

Piracy and maritime security in Southeast Asia

by Vinita RamaniPiracy is as old as seafaring itself and some of the world’s hotspots for pirate attacks are also the main trade routes for global oil transportation. From the Straits of Malacca and Singapore to the South China Sea and beyond, who are the pirates of Southeast Asia and what do they want?

A 1658 map of the Indian Ocean, or Erythraean Sea, as it was in antiquity. Composed by Jan Jansson after a similar 1597 map published by A. Ortelius. Wikimedia Commons.

The word “pirate” conjures a contrast of images in the mind. We picture a ragtag group of Somali men with rocket-propelled grenades and knives. Or we think of machete-wielding Sumatran pirates waiting to attack ships in the crowded Strait of Malacca. On the other end of the spectrum, pirates are romanticised as outlaws, or bohemians in mainstream cinema. Most accounts of piracy — whether fictional or factual — are decidedly European and largely limited to the Atlantic and Mediterranean oceans. Even the words “pirate”, “privateer” and “corsair” describe the conditions of maritime trade from a European expansionist perspective.

But in the coastal societies of Asia, seafaring, commerce and piracy have always been intimately connected. A 5th century Latin map, the Tabula Peutingeriana, famously warns of pirate-infested waters in southern India. In the 13th century, Chinese traveler Tchao Jou-Koua described how the Sriwijaya kingdom — a maritime power — exercised control over the region, by sending out boats to attack ships that did not dock at its ports. Commercial warehouses in Malacca, Johor and the Riau Archipelago grew under Muslim sultanates with the assistance of pirate communities.

If maritime commerce, nation-building and piracy have always been inextricably bound, that is no less true today. In 2018, the total world petroleum and other liquids supply hit a whopping 99.92 million barrels per day. Over 60 percent of that travels through the sea.

The Strait of Hormuz

Situated between Oman and Iran, the Strait of Hormuz is the vital starting point of this daily oil flow. In 2016, trade out of the Strait was at 19 million barrels per day making it the world’s busiest and most important oil chokepoint. At its narrowest, the Strait of Hormuz is just over 10km wide, accommodating two shipping channels and a buffer zone. Over 80 percent of the oil that moves through this chokepoint finds it way to Asian markets. China, Japan, India, South Korea and Singapore are the main destinations. Tensions in the Strait are not uncommon and any attacks on tankers here can cause oil prices to surge when markets get rattled by political instability.

The Strait of Malacca

The Straits of Malacca and Singapore (SOMS) is the second most important global chokepoint, with over 16 million barrels per day traded in 2016. More than 120,000 ships sail through its narrow channels each year. The Phillips Channel in the Singapore Strait is just 2.7km wide making it a maritime zone of bottlenecks and potential oil spills or collisions. Historically, the Straits of Malacca and Singapore have also seen significant incidents of armed robberies at sea. Some of this is caused by fluctuations in global crude prices and slow economic growth. During such periods, tankers end up idling off ports at this busy chokepoint, waiting for the next job. With so many vessels in the crowded Singapore Strait, there is often an increase of incidents. This is why there was a spike of armed robberies in 2014.

The oil market has an annual production value of US$1.7 trillion. But about US$133 billion worth of fuel is stolen and enters the black market each year. Much of that theft occurs at sea. Oil trafficking is a major problem in Southeast Asia, where at least 3 percent of the oil accessed by consumers is from the black market.

From the Straits of Malacca and Singapore, ships make their way to the South China Sea. Much of the Middle East relies on Asian markets for its exports and over 70 percent of its crude oil shipments pass through here. That trend is set to continue — the world’s biggest importer of crude oil is now China, surpassing the United States.

Crimes at sea, just like crimes on shore, take on many forms. They can range from robbery (armed and unarmed) at one end of the spectrum, to kidnapping for ransom and hijacking on the other end.

The bulk of incidents in this part of the world are defined as “armed robberies at sea” and not piracy. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) defines piracy as illegal acts that are committed “in a place outside the jurisdiction of any State.” The International Maritime Organisation defines armed robbery as any act, other than piracy, which is directed against a ship that is within a State’s jurisdiction. Pirate attacks happen on the high seas, whereas armed robberies occur within the territorial waters of a country.

Crimes that happen at sea, according to UNCLOS maritime zones

Though common sense says that robbing tankers, tugboats, and ships so close to a port should be riskier, many countries in Asia (particularly Indonesia) are archipelagos, or a cluster of islands. The marine waters enclosed by these islands (called archipelagic waters) are hard to monitor and offer a safe haven for pirates.

Regional tensions fuelled by competing claims for territorial waters make it difficult to establish protocols for maritime security. Various organisations, like Stable Seas, the International Maritime Bureau’s Piracy Reporting Centre, and the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (ReCAAP) combat piracy.

Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand also came together in 2006 to initiate the Malacca Straits Patrol (MSP). Rivalries persist but the efforts have paid off, with a decline in incidences across Southeast Asia due to better law enforcement. But new types of crimes may have emerged. High-value tankers can be targeted if cyber criminals acquire information from company servers, or if ship officials are complicit and give up information to pirates about the ship’s position or the cargo onboard. Insurance fraud is common. Ships submit fake reports of attacks to get insurance pay-outs, or qualify for “risk pay” bonuses.

In 2018, out of 98 incidents in Asia, four were defined as acts of “piracy”, which means they took place in international waters, or the “high seas”. “Armed robberies at sea” make up the bulk of incidents because they often take place when ships are either at anchor or underway from a port, in territorial waters. In the crowded shipping lanes of Asia, they make for easy pickings. Armed with a parang and some knives, small raiding parties can try their luck to steal personal effects from the crew, siphon oil, or grab a dinghy boat. These are opportunistic robberies and the stakes are not high.

In ports like Chittagong, Bangladesh, port congestion also triggers robberies. Ships have to wait for days or weeks to offload at port, and a complacent crew is ill-prepared for robbers who are ready to board and rob the ship. Armed with firearms and knives, they steal ship’s stores such as drums of paint and oil, and mooring ropes. The Sundarbans — one of the largest mangrove forests in the world — is also rife with bahinis (pirates gangs), and kidnappings are common. In 2018, 56 fishermen were kidnapped in four incidents.

While piracy and armed robbery of ships is on the decline in Asia, the threat of kidnapping for ransom and hijackings is still present. The difference between piracy and all other types of maritime incidents is primarily a legal one: they only tell us where the crime took place. But they do not describe the severity of the crime.

In Southeast Asia, maritime terrorism by violent non-state actors is heavily concentrated in the Sulu and Celebes Seas, and the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) is the main perpetrator. An Islamist separatist organization, the ASG purportedly fights for an independent Muslim state in southern Philippines. Its main mode of attack involves kidnapping for ransom.

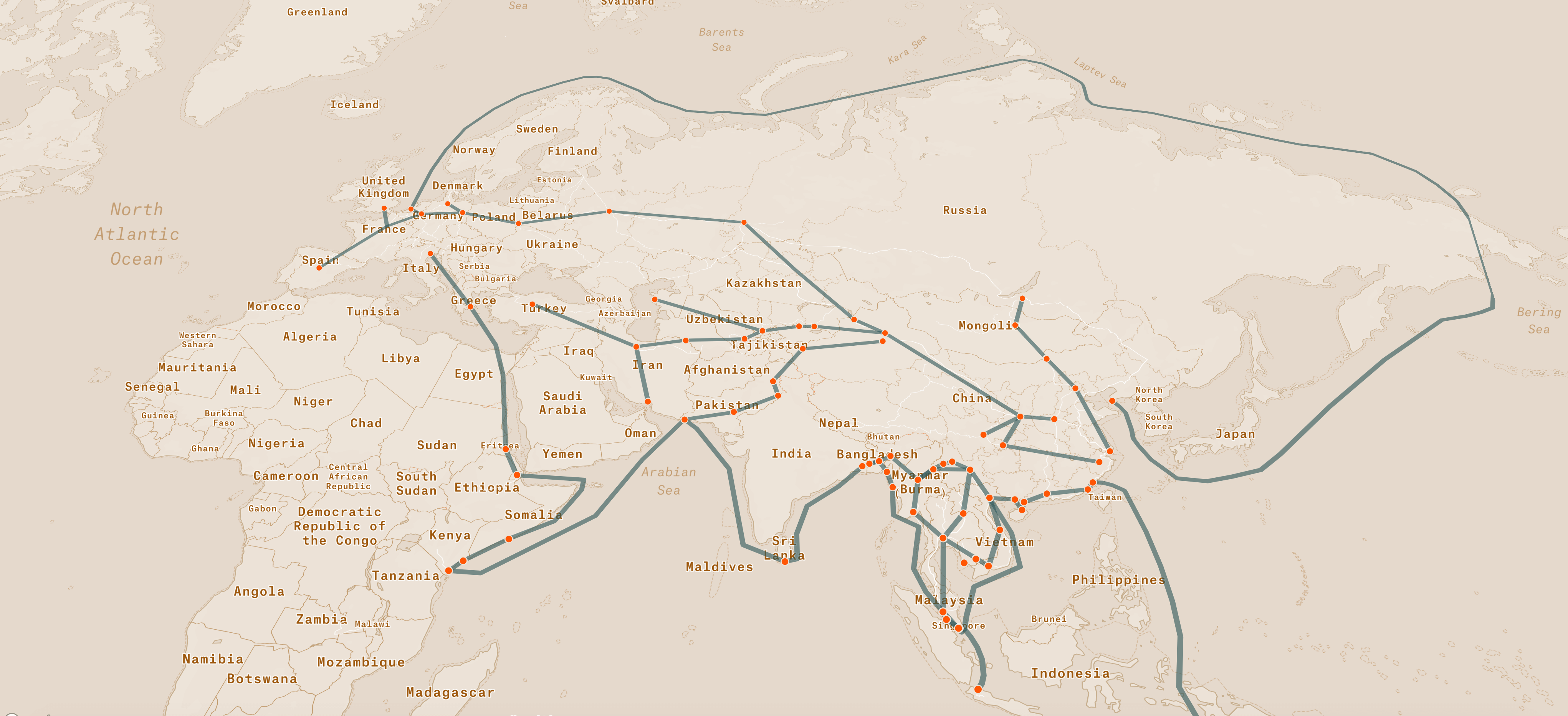

Sea routes used by fighters to join the Abu Sayyaf Group. Image credit: Stable Seas

The ASG has recruited fighters for its cause from Indonesia and Malaysia, prompting Malaysia to establish the Eastern Sabah Security Command (ESSCOM) in 2013. The ASG’s methods have included producing intimidating videos that are widely publicized to demand ransom payments. Six hostages have been beheaded since 2014. With the spike in incidents and the trauma that seafarers face during violent hijackings, the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia formed a Trilateral Cooperative Agreement in 2017 to engage in maritime and aerial patrols.

Sama-Bajau children in Basilan, Philippines. The Sama-Bajau are the dominant ethnic group in the islands of Tawi-Tawi, Philippines. From the Sulu Archipelago to Mindanao, northern and eastern Borneo, they are known as “sea-gypsies” and have been widely mentioned in historical accounts of piracy and sea raids. Wikimedia Commons.

Maritime insecurity does not happen in a void. Southeast Asia’s pirates and armed robbers live in a region that is replete with natural resources and much of it is in the blue depths of Asia’s oceans and seas.

Yet, economic development across the region has left millions behind. Where coastal communities should thrive in these “blue economies”, they face high levels of poverty and environmental degradation. Nearly 85 percent of the global population working in fisheries and aquaculture is found in Asia. But Asia’s waters are seriously overfished and ongoing Illegal, Unregulated and Unreported (IUU) fishing in disputed areas like the South China Sea will hurt the populations depending on these waters for their livelihoods.

North Sumatra, Jambi and Riau provinces in Indonesia are among the poorest in the country. The Strait of Malacca skirts along these provinces and the pirates here are often just young, idle and poor. Others migrate to special economic zones in Batam and Riau Islands, hoping to get jobs, but end up in pelabuhan tikus (rat harbours), and struggle to make ends meet. Pirates in such situations are often a “Robin Hood” figure: a seasoned fisherman who raids ships with a small crew and uses the money to build mosques for the local kampung.

Southeast Asia is also home to the Coral Triangle, a 6-million square kilometre ecosystem which supports the livelihoods of more than 100 million people. But not everyone living in this ecosystem benefits from it. The Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) in the Philippines, ranks the last in economic development in the country. Thirty percent of the Philippines’ poor live in Mindanao alone. If this restive region is left behind, the pirates here will be the greatest threat of all to maritime security and prosperity in Asia.

Stable Seas, a program of One Earth Future Foundation, engages the international security community with novel research on illicit maritime activities such as piracy and armed robbery, trafficking and smuggling in persons, IUU (illegal, unreported, and unregulated) fishing, and illicit trades. By understanding how these activities perpetuate organised political violence and threaten economic development and coastal welfare, the unique research products developed by Stable Seas seeks to aid policy development and contribute to maritime security.