Money flows:

Who's investing in Laos, and what problems do they present?

by Pei Ying Loh & Zenn WongA nation disadvantaged by geography, Laos has turned to intense infrastructural development and foreign direct investments to accelerate economic growth. As the landlocked nation opens its doors to foreign money, who is it inviting, and what troubles lay ahead?

Once an ancient kingdom and a hub for overland trade, Laos has found it difficult to thrive in a globalised world, after decades of colonisation and war. The country’s mountainous terrain and modest population of 7.2 million have also left it with limited economic opportunities. To solve this, the government has generously welcomed foreign direct investments (FDI) since the 1980s, especially in major infrastructural developments, hoping to leverage capital and skills transfer to improve its economy.

Souce: World Bank

In the last two decades, FDI into Laos has seen a steep and unwavering climb. The country has also passed legislation to promote itself as an ideal market for foreign investments. Among these measures are enacting an Investment Promotion Law that permits foreign companies to set up wholly-owned enterprises or joint ventures, removing barriers to trade and entry such as eliminating a minimum capital requirement, and allowing foreigners to own property.

Laos is not unique in its pursuit of foreign investors. For most decolonised countries, FDI is a bastion of opportunity and economic growth, and for some, it has indeed transformed society. But in recent years, FDI has also been touted as a poisoned chalice as countries become increasingly reliant on them, subjected to the influence of investor countries.

It is important to understand the origins and size of FDI inflows into Laos. What do these foreign investments look like? What companies are involved, and what type of projects are they involved in?

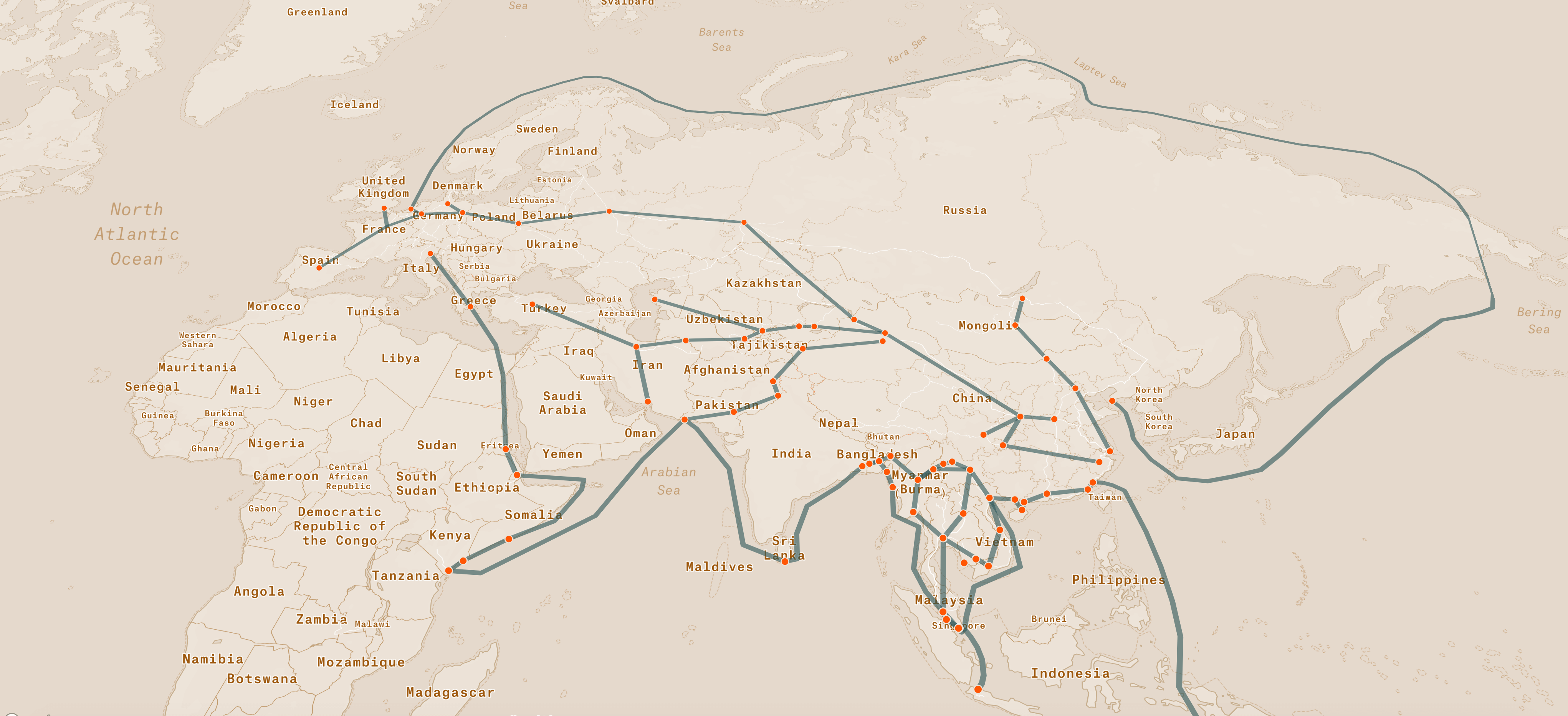

The most expensive foreign investment project in Laos right now is the China-Laos High Speed Railway. At 422 kilometres in length and costing US$6.8 billion, it is the priciest and largest megaproject to ever be built in Laos. It spans from the capital Vientiane to the town of Boten, which borders Yunnan, China.

Given the massive scale of this project, this cost is not unexpected. There are high aspirations for it, too—it will transform Laos from land-locked to land-linked. There is great hope that the heightened connectivity will bring about plenty of benefits such as reduced logistic costs, inflows of foreign investments, and tourism.

But the China-Laos High Speed Railway has become symbolic of what’s wrong with Laos’ foreign investments landscape and projects. While the project’s funding and ownership was split 70-30 between China and Laos, Laos still struggled to foot its part of the bill. It further took a US$480 million loan from China’s Export-Import Bank. If Laos fails to pay its debt, the railway will more or less be China’s, at Laos’ expense.

Many more are scattered across the country. These are concentrated mainly in the south and northwest, regions traversed by many rivers and tributaries. Majority are energy infrastructure that capitalise on Laos’ vast river network.

Laos has long wanted to be the “Battery of Southeast Asia”. At present, Laos exports about two-thirds of the electricity generated from hydropower. Electricity is its top export at US$1.93 billion, almost a third of its total exports. Most of these hydropower projects are still in development, and as climate change becomes a more pressing concern, more Southeast Asian countries will turn to Laos as a source of clean, renewable energy. For example, the ASEAN Power Grid is already underway, with ambitions to transmit power from Laos to Singapore.

Naturally, this ambition is also demonstrated by the sizable number of foreign investments into transmission projects. These are crucial in moving the electricity from the remote locations of these hydropower dams to load centres, both within and outside Laos.

There have been over 360 infrastructural developments since 2006 that have received foreign funding in Laos. The lion’s share of foreign investments are in energy projects, at an estimated 262 projects.

The next largest sector for foreign investments is transport, which is likewise unsurprising for a landlocked country. While the China-Laos High Speed Railway is by far the most expensive project in this sector, most of the projects are in developing roads.

Only a handful more investments trickle in other miscellaneous sectors, such as a stadium and irrigation dams, among others.

With the numerous energy projects, it is expected that this would be the most expensive sector. These energy projects cost an estimated US$49 billion, and some of the priciest investments have yet to be built. They are either planned or under construction, a nod to the recency of the nation’s growth in foreign investments in hydropower.

In contrast, although the China-Laos High Speed Railway is the country’s most expensive project, the total known cost of the transport sector is significantly less than the energy sector. The transport sector sees overall less investments in volume, scale, and uniformity. Most of these are either relatively cheap or extremely expensive.

A complex web of companies form the infrastructural landscape in Laos. Many of these projects are deeply connected by way of similar investors and contractors, and many projects have multiple stakeholders.

Most of the companies involved in these projects are private enterprises, joint ventures, and state-owned companies. The private companies are from a wide spectrum of countries, such as Thailand, South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, and a number of European countries. Most of these firms specialise in construction or energy, such as Thailand’s Ratchaburi Electricity Generating Holding PCL, or Austria’s Andritz Hydro GmbH.

Joint ventures account for a fair number of these companies. They are project-specific enterprises, created between a Laotian company and a foreign investor. Most of them are joint ventures between Électricité du Laos, Laos’ state-owned energy company, its subsidiary EDL-Generation, and external investors.

State-owned enterprises make a big appearance in these projects. This is not surprising considering that its communist neighbours, Vietnam and China, are amongst Laos’ biggest investors. However, China’s state-owned enterprises are overwhelmingly represented in the profile of companies investing in Laos. For example, China’s Export-Import Bank is involved in 22 projects, while Sinohydro is connected to 15.

The primary investors in Laos are China, Japan, Thailand, and Vietnam. While these investments are made to a common end, the shape and form in which they take are very different.

Given that the vast majority of these are hydropower projects, the scale of development has a very significant impact on Laos’ society and landscape. Hydropower development has been promoted as a clean, sustainable way to potentially meet both the energy and economic development needs of the nation of Laos, outweighing any potential costs. However, for the people in Laos, the pursuit of such development has so far resulted in unsustainable outcomes.

The implementation of hydropower building has resulted in land clearing, forced evictions, displacement, and loss of land. In addition, free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) has not been achieved, which has impacted Indigenous Peoples, who report a loss of cultural identity. Furthermore, the dams impact those beyond Lao’s borders, with effects communities have not been completely consulted on. The change in the mighty Mekong River’s flow and loss in biodiversity have affected the food security of those who are dependent on the river for their livelihoods.

Just as pressing a concern is Laos’ disproportionate reliance on Chinese financing and investment. Although Thailand is Laos’ biggest hydropower investor, China is Laos’ largest investor overall—Chinese money supports not just hydropower, but also capital-intensive projects in natural resources, agriculture, mines, rubber, and other large infrastructure like railways. Accompanying this development is a steadily increasing government debt. While many countries have a high public debt, they also have proven abilities to keep up with their debts. Laos is exceptional in its vulnerability in relation to China.

China’s imposing presence on the investment landscape warrants closer inspection, and not simply because of the sheer volume of money. All of these developments are arguably beneficial to Laos, if the benefits eventually reach the people of Laos. A large number of these projects operate on the Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) scheme, which allows the host government to obtain infrastructure at a lower cost in exchange for the partnering contractor operating and owning the asset for the first 20 to 40 years. The risks that Laos takes on are great—costs may overrun, technologies get outdated, or poor maintenance depreciates the value of these assets.

Overly optimistic demand projections, reduced operating performance due to drought, low tariff rates, and risky contracts are simply a handful of many things that may lead benefits to be well below what has been projected. Similarly, there is little evidence that any actual benefits of such projects have reached the poorest in the country. These projects are also supposed to create jobs for locals, and help build a skilled workforce. Yet, unsurprisingly, China’s state-owned companies are often awarded the contracts for these developments, with little guarantee that these will lead to jobs for locals. All this, for the production of electricity that isn’t even being used to light Laotian houses, but is instead being sold to Thailand.

As Laos goes into deeper debt, it also brings about higher economic uncertainty, which disadvantages the country’s bargaining abilities. Yet, it has shifted life in Laos, from turning Chinese language into a desirable learning educational route, to increasing anti-Chinese sentiment, while also shifting the geopolitical balance of the region.

In 2018, the dam at the Xe Pian-Xe Namnoy hydropower plant collapsed. It flooded neighbouring villages downstream. 71 people were killed, 19 villages decimated, and some 14,000 people displaced. Three years later, many of these victims have yet to be satisfactorily compensated, and many are still awaiting for their new homes to be built.

In theory, FDI should bring about economic growth and opportunities for countries like Laos. This episode, amongst others, illustrates how bad the consequences can be if FDI deals are done unsustainably. There is also little evidence that the wealth that China and others have poured into the country has successfully trickled down to the rest of the population.

It also raises the question on accountability. Should a project go awry, who bears the burden of addressing the fallout? Not much is known about the exact nature and agreements of these investments. It is challenging to locate details about these projects, both inside and outside of the country. This makes it difficult to keep actors—investors, contractors, manufacturers—accountable for their actions.

This is why the work of initiatives such as Reconnecting Asia, AidData, CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems, Stimson, and Open Development Mekong are so important. They are diligently compiling and sharing information about infrastructural developments in the region, and studying its impact. Their efforts to keep data open and accessible, in a data-scarce landscape, is crucial for accountability and sustainability.

It is inevitable that Laos will need to grapple with China’s investments, and the country’s whims and wishes for the foreseeable future. This was evidenced to some degree with the COVID-19 pandemic, with Laos being completely reliant on China for its donated vaccines. Chinese investments are unavoidable, and moving forward, can only be managed. But to do so successfully, Laos, and all those interested in its future, will need more information.

Disclaimer: ODM makes no representation or warranty, either expressed or implied, in fact or in law, with respect to the accuracy, completeness or appropriateness of the data, materials or documents contained or referenced herein or provided. The views expressed in this story are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of ODM.

Open Development Mekong launched as an integrated regional open data platform in 2015. The ODM signatory approach relies on impartial presentation of data, using open data standards alongside objective analysis through visualisations, briefings, maps, and other data products to increase transparency and accessibility. The platform has since evolved into a network supporting data and digital rights that are reflective of and accessible to all citizens across the Mekong region. Our target audience of civil society, private sector, government, academia, and marginalised communities utilise ODM's rich repository of data and information to support research, analysis, and decision-making.

Zenn is a data scientist with a penchant for all things urban. She is fascinated with the use of smart city frameworks and open data in promoting development. When not fiddling with anything data-related (and sometimes even while doing so!), she enjoys the outdoors, good electronic music, and a refreshing cup of white tea