Is foreign investment truly a force for good?

by Zafirah Mohamed Zein

Foreign direct investment has been heralded as a tool for fueling economic growth in developing countries like Cambodia. But its impact on local livelihoods and ecosystems leaves us questioning whether it is all that it’s made out to be.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) happens when foreign investors enter another country to operate or expand their businesses. Many of these businesses are multinational corporations that want to take advantage of low labour costs and weaker environmental regulations in other, usually developing, countries.

In Cambodia, many FDI projects are located in Special Economic Zones (SEZs). SEZs are a type of economic land concession that gives foreign investors special privileges and subjects them to different laws and regulations than in other parts of the country. The economic land concession model can be traced back to French colonial rule, when large tracts of land in colonised lands were used to grow rubber and other cash crops.

As of September 2020, 46 SEZs have been recorded across Cambodia.

FDI makes up a significant proportion of Cambodia’s gross domestic product (GDP). Long touted as an important driver of economic growth, FDI serves as an alternative source of financing and an opportunity for developing countries to build key infrastructure and provide new jobs.

The host country may further benefit from new skills, technical innovation, and management expertise that foreign companies bring. Landscapes and communities typically end up more built up and better connected through new roads, bridges, ports, and telecommunications networks set up to support these businesses.

The steady stream of FDI into Cambodia has contributed to developing key infrastructure, commercial and residential real-estate properties, and booming manufacturing and agro-processing sectors.

Many developing countries court FDI through policies that entice foreign companies to work. In the 1990s, Cambodia opened itself up to international trade and restructured its economy to become more appealing to investors after a protracted civil war and years of instability.

Thanks to Cambodia’s stable political and economic climate, open market, and numerous FDI incentives, the country has seen an upward trend in foreign investment projects. Net FDI has nearly doubled in the past decade. Between 1995 and 2015, Cambodia’s economy grew rapidly, with FDI encompassing a higher proportion of its GDP relative to other countries in Southeast Asia.

How big are the investments in Cambodia's special zones?

In 2020, the Council for Development of Cambodia approved 21 new investment projects, most centred around the construction of luxury hotels, business centers, and large agricultural farms managed by Chinese firms.

Multi- and transnational companies handsomely profit from the low costs of conducting business in Cambodia and the various government incentives. They enjoy the permission to fully own a business, take up a tax holiday of up to eight years, and rely on dispute mechanisms to manage conflicts with the local population. Locals, in contrast, are not extended the same rights and resources.

While these benefits make doing business in Cambodia attractive, some countries or companies might be dissuaded by the country’s relatively small market size and limited pool of skilled labour. Other factors that might dissuade foreign investors include rampant corruption, high energy costs, and a lack of transparency in government processes.

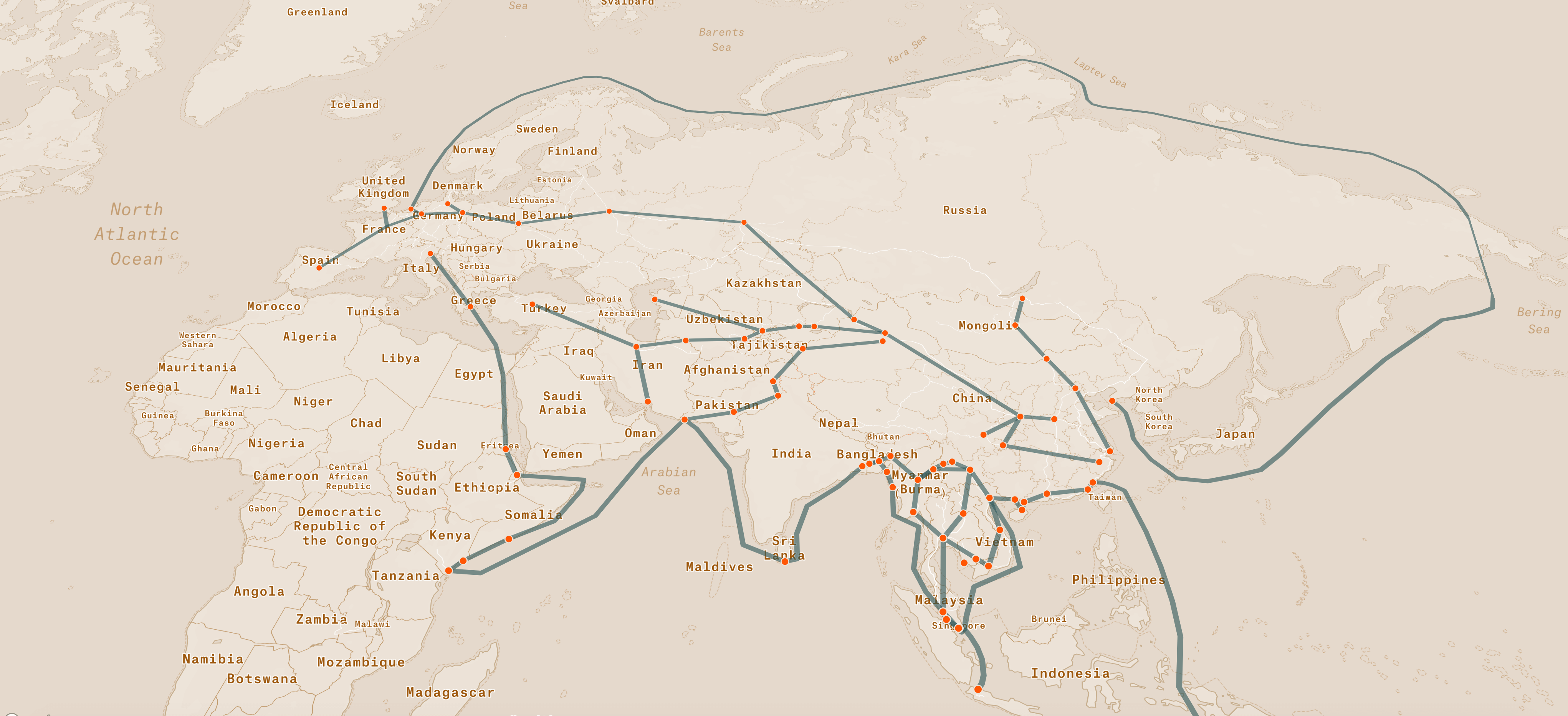

Asian powerhouses China, South Korea, Japan, and Singapore are among Cambodia’s top investors, with China taking up a significant share of all FDI in the country. China has pumped $5.8 billion into building roads, bridges, airports, and hydropower dams in Cambodia as part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Many of these investments are financed by interest-free and concessional loans from China Eximbank, to which Cambodia has an outstanding foreign debt of around $3.4 billion.

In 2018, 43 percent of the US$3.6 billion in FDI originated from China. Chinese money has transformed once-sleepy towns and lively fishing villages into tourist hubs.

Although SEZs are intended to boost local employment and redistribute wealth to rural areas, Chinese-run projects have been described as “classic enclaves” operated by private companies that contribute little to the local economy. While most FDI ventures manufacture export goods for foreign markets, Chinese businesses also often import the materials needed for production instead of procuring them locally. It seems that Chinese investment has locked Cambodia’s economic growth into a closed loop leading back to the homeland.

According to a report on investment in Sihanoukville, at least 60 percent of the local population is negatively affected by Chinese development. Not only do Chinese companies have free rein over how they develop a SEZ, they are also allowed to open informal businesses once run by locals, such as massage parlors, restaurants and food stalls.

The lucrative prospects of doing business in Cambodia have attracted more Chinese nationals to take up work and residence in the country. In the coastal province of Sihanoukville, Chinese people now make up 20 percent of the population. Their growing presence has been accused of diluting local culture, transforming the native environment, and causing rent prices to soar.

Unable to compete with these new Chinese businesses and to afford rising rent prices, many locals have been forced to migrate to other areas.

Foreign direct investment comes with the promise of jobs and development-driven growth—but this has come at a cost to Cambodians.

A sign bars visitors from the beach unless they are guests at Independence Hotel at Sihanoukville’s Independence Beach on November 30, 2020. (Danielle Keeton-Olsen/VOD)

The tension between foreign investment and local communities is most deeply felt in Sihanoukville province, where coastal marshlands and beaches that stretch for miles have attracted Chinese tycoons to turn once remote villages to mega tourism developments.

A reported 52 companies are invested in the province—90% percent of them Chinese. Valuable coastal land has been parceled up and given to powerful government officials and businessmen through a slew of FDI deals. In 2019, the government granted a tourism company 400 hectares of sea to develop a new, lucrative coastline. Each day, local villagers face threats to their livelihood as the company pours sand into the sea, destroying the marine ecosystem.

From 2008 to 2010, so many families have been evicted from their homes in Sihanoukville that the province ranked first place in land dispute cases recorded by an international non-profit. Hundreds have been forcibly evicted from their homes without compensation, denied claims to the land they have depended on for decades. As foreign businesses overwhelm the local landscape and the promise of new jobs dims, Cambodians are now doing what the government had aimed to prevent through FDI: migrating elsewhere in search of work.

* Interviews from the Cambodian Center for Independent Media.

Shop owner Yang sells her wares from under a bridge after workers kicked her out from a spot along the road above, she said on December 1, 2020 in Preah Sihanouk province’s Prey Nob district. (Danielle Keeton-Olsen/VOD)

If no serious action is taken, in the future more Cambodian people will lease and continue to close their businesses in Preah Sihanouk province. First, Cambodian people cannot afford the property; second, now more people have left.

- Mr. Sreng Vanly, Preah Sihanouk provincial coordinator for the Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights.

It was fairly lucrative in the past, but it’s [income] very low now. With the higher price of squid, I still sell it at the same price. The prices of all goods have increased. The goods’ prices increase because if we get up late, the Chinese take it all over. They buy for consumption and sale in Chinese restaurants. There are no Cambodian tourists, but only construction workers. There are less tourists from Phnom Penh because the guesthouse rates have risen.

- Ms. Chorn Bork, a seller of grilled squid on O Chheu Teal Beach.

A fisherman drives his boat past the Kampong Samaki community fishery, with members saying he was carrying illegal nets, in Kampot’s Kounsat commune on August 25, 2021. (Danielle Keeton-Olsen/VOD)

In Kampot province, local fishing communities depend on the sea to survive. Communities of small-scale fishermen have relied on coastal resources for centuries, to generate income and continue customary ways of living. But large development projects such as the French Riviera Marina—a sprawling multi-purpose tourism resort and marina—are destroying marine life and depriving these traditional communities of their primary source of livelihood.

Fishermen have reported increased pollution, destruction of mangroves, landfilled beaches, and dwindling fish stocks. Even families who do not directly depend on fishing have expressed loss over the arrival of large scale developments and the growing number of tourists.

Although traditional community fisheries are recognised by the government, no law or safety mechanism protects them from land dispossession. Fisheries are considered state land, which leaves them open to being swallowed by lucrative business interests.

Truck tracks and sand cut through a strip of mangrove forest near the IGB (Cambodia) sandfilling site, in Kampot’s Toek Chhou district on August 26, 2021. (Danielle Keeton-Olsen/VOD)

If the coastal area land filling happens, various types of ecological life such as seagrasses, corals, mangroves, and family fishing will be impacted. We have gone fishing around the coastal area since our ancestors, and if the coastal area land filling happens, what will we do? Income we earn from fishing is to mainly support our children’s education.

- Mr. Tith Rin, leader of the Trapaing Ropov fishing community.

I say that only fishing can help our people, and it is our Khmer culture that we have the sea, we have the coast, we have sea species, we have mangroves for helping all of us. If we allow others to land-fill [sea spaces], we don’t know what we will count on for survival. We will have to leave villages to work in other countries and we will leave our villages behind.

- Mrs. Pon Nhu, head of the advocacy network committee of Trapaing Ropov fishing community

* Interviews from the Cambodian Center for Independent Media.

Growing interest in nature-based and eco-tourism has led to increased encroachment into remote, rural, and conservation areas—all part of the government’s plan to reel in more tourists while encouraging connectivity and infrastructure in underserved regions.

The Cambodian government has granted foreign investors numerous land deals to develop new tourism hubs around unique local attractions, such as floating villages, fisheries, and national parks. Areas rich in natural heritage and biodiversity are now under threat of being devastated or wiped out completely.

The negative impacts of these foreign-funded developments are harsh on communities living within or close to special economic zones. Their lives are dependent on their environment, and they are likely more vulnerable to the loss of natural resources and climate change.

Larger investment projects, such as those in mining and agriculture, tend to overexploit people and natural resources more than smaller developments. While the Cambodian constitution stipulates the need to protect the environment, weak regulation and corruption has kept both nature and people on the losing end of foreign investment.

As the cases of Sihanoukville and Kampot show, FDI does not always live up to the benefits it promises. While FDI might very well bring about economic growth and much-needed capital to a developing country like Cambodia, it also invites higher levels of pollution and ecological damage. Locals are the first to be impacted by these changes in land use. Many end up from experiencing health issues associated with living close to piles of toxic waste and polluting power plants.

Environmental laws or services are typically weaker in developing countries because they are not as well-enforced as wealthier, more developed nations. After all, many countries in Southeast Asia started development with fewer high-polluting industries, and thus had little demand for such regulation. This makes countries like Cambodia a haven for transnational companies seeking to evade strict laws and maximise profit.

This is nothing new. Multinational companies have been known to outsource the dirty parts of their production to poor countries in Asia and exploit the region’s abundance of cheap labour. Local protests against new carbon-intensive factories and wage strikes against large plantation owners expose the inequality that underlies global FDI flows.

Greater global awareness of these injustices and increased media attention on China’s BRI has driven a few developers to enhance their image by making more commitments to corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the environment. In theory, this should remedy the ills caused by their projects and benefit the local population through providing education, healthcare, and social security.

But while companies may be required to fulfil their CSR commitments and carry out rigorous socio-environmental impact assessments before constructing their projects, many only relay their studies to the authorities and local communities after the foundations have already been laid.

It is also uncertain whether foreign companies put into practice their plans to mitigate harm and engage the community—and what their effects actually are once implemented. There is currently no universal best practice on how best to organise environmental management; this leaves corporations and governments much room to tailor such initiatives to local contexts, but also makes it hard to ensure that they do not make things worse.

It depends. Whether FDI leads to sustainable development in Cambodia depends on the quality and quantity of FDI entering the country. Economies with too much FDI in their GDP risk being overdependent on foreign countries, which can end up crippling domestic markets. Where foreigners drive locals out of their homes and jobs, countries might struggle even more to build strong and sustainable local enterprises in the long run.

No doubt, FDI brings real benefits. It contributes directly to economic growth and opens up access to foreign markets. Incomes may rise, and developing countries are given opportunities to improve business capacity by absorbing new skills and technology that cannot be bought through trade.

But while this appears to level the playing field between developed and developing nations, we must not forget that FDI’s negative impacts widen the gap between rich and poor, both between and within countries. This happens because foreign investors are often inconsistent in meeting the sustainable development goals of the host country, and many go overseas so they can operate at lower social and environmental standards than they could have back home.

So, the deck remains stacked against many developing countries in need of investment. Unequal global power structures between rich and poor countries tend to favour investing corporations to the detriment of the host. For FDI to generate sustainable and equitable growth, Cambodia must strike a precarious balance: attract foreign investment, yes, but only if its costs are not too high for its people and environment to bear.

Open Development Cambodia (ODC) is an ‘open data’ website, the first of its kind in Southeast Asia. It does not promote any particular perspective, agenda, or bias other than providing objective information about Cambodia and its development. ODC makes complete and reliable data and information publicly available for everyone and presents it in user-friendly and understandable formats. The ODC hopes that the site and the data will facilitate research and communication between the public, private companies, civil society, and governments.