Southeast Asia’s air conditioning is burning up the Earth

by Kenneth Wee

Few things feel better than a gust of chilly air when walking into a mall on a hot day—especially now that the dry monsoon season is here. But most air conditioned buildings in our cities are too cold—and they’re burning up the planet.

Air conditioning brings relief from the heat all over the world—and nowhere more so than in the tropics. Lee Kuan Yew, the esteemed former prime minister of Singapore, had this to say about air conditioning:

"Air conditioning was a most important invention for us, perhaps one of the signal inventions of history. It changed the nature of civilization by making development possible in the tropics.

Without air conditioning you can work only in the cool early-morning hours or at dusk. The first thing I did upon becoming prime minister was to install air conditioners in buildings where the civil service worked. This was key to public efficiency."

Lee’s comment shows how crucial air conditioning is to the region. In the tropics, the combination of high temperatures and humidity can be frustrating at best and deadly at worst. All over Southeast Asia, homes, offices, malls, and other public spaces use air conditioning to keep people comfortable and productive.

What’s more, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs)—plausible future scenarios of how greenhouse gases and other human activities will affect the climate—the tropics are getting even hotter. Under RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 (under which humanity makes some effort and no effort to curb emissions, respectively), global warming may raise average temperatures in Southeast Asia between 1.6 and 3.0 degrees Celsius by 2100.

Global warming could also put a billion people in Asia in the path of deadly heat waves by 2050, making access to air conditioning—which can protect people from heat injury—a matter of survival.

ASEAN is barely hanging on in the surging heat. Just 15 percent of households in ASEAN own an air conditioning unit, and ownership varies widely with income across the region. More than 80 percent of people in wealthier countries (e.g., Singapore, Malaysia) own an air conditioning unit. In less wealthy countries (e.g., Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines), only 10 percent do.

ASEAN’s cooling needs will surge with the region’s urbanisation and growing middle class. Household energy use in ASEAN is expected to rise by 64 percent by 2040 due to air conditioning alone—not counting the impacts of COVID-19 and accelerated work-from-home trends. Even before the pandemic, the International Energy Agency—a highly regarded forum that tracks and recommends on energy trends and policy—reported that by 2040, cooling will account for nearly a fifth of the region’s total energy needs and up to 30 percent of peak electricity demand (200 GW), if current and planned policies stay the same.

Put in context, that’s all of Germany’s current electricity capacity.

It all begins with Willis Carrier, an engineer in the United States. Carrier invented the first air conditioning (AC) unit in 1902 to control humidity in his company’s paper plant, but he quickly realised that it could help make indoor environments more comfortable. AC soon spread to American theaters in the 1920s, giving rise to the “summer blockbuster” as people flocked to movie theaters to escape the summer heat.

A decade later, the first room AC units were developed. In a modern air conditioning unit, warm air passes over coils filled with refrigerants—chemicals such as hydrofluorocarbons (HFC) that absorb heat when they evaporate. An electric compressor uses high pressure to turn the HFCs back into liquid, expelling waste heat in the process. The refrigerant is then pumped back into the coils to cool more warm air.

The sheer amount of air conditioning in ASEAN comes at a real cost to the environment.

As Asia’s air conditioning drives much of the region’s need for energy, accounting for up to 60 percent of overall electricity demand in urban areas with hot climates. Given that around 75 percent of Southeast Asia’s energy still comes from non-renewable energy sources at present, air conditioning’s consumption of fossil fuels will grow rapidly and unsustainably.

The use of HFC refrigerants in air conditioning units makes things even worse. HFCs were meant to replace compounds that deplete the ozone layer, but they are also among the world’s most potent greenhouse gases. Currently, their impact on global warming is small, but their atmospheric concentrations are soaring as more air conditioning units hit the market in Asia.

If we stick to business as usual, Lee Kuan Yew might just have been prophetic: air conditioning’s effect on climate change will truly change the course of human civilisation.

Turns out, that’s far less the case than one might think.

In many countries in Southeast Asia, offices and public spaces, such as cinemas and malls, are cooled so much that their occupants feel chilly. This is especially so in affluent, urbanised countries such as Singapore, where many buildings have cooling systems designed with an excess peak output of close to 40 percent.

Overcooling buildings makes sense for worst case scenarios, such as heat waves or equipment breakdowns. But most days, these cooling systems do not respond to changes in the weather outside, using up lots of unnecessary power. Wet monsoon seasons, for example, turn already cold buildings into freezers—resulting in building occupants wearing sweaters in the tropics.

Even our buildings themselves are often ill-suited to tropical environments. Western architectural ideals—such as the International Style of skyscrapers—were widely adopted as a symbol of modernity in the 1970s as Asia grew economically. But glass facades demand lots of energy to cool due to their greenhouse effect, and developers often turn to air conditioning for the job. Double-glazed windows and laminated glass help, but they need frequent replacement and are hard to recycle. For these reasons, even the West is turning away from skyscrapers these days.

Air conditioning’s waste heat also adds to the urban heat island effect (UHI), in which human activities make urban areas much warmer than rural areas. For Asian and Australian cities, the UHI can add between 0.5 and 11 degrees Celsius to ambient temperatures, with an average close to 4.1 degrees. This creates more demand for air conditioning use, fueling a vicious cycle of indoor cooling and outdoor heating.

Technology does offer some promising solutions. The National University of Singapore has developed AC units that use water instead of HFC refrigerants, consuming around 40 percent less electricity. In 2020, an international group of researchers successfully tested a radiant cooling system—which absorbs our bodies’ radiative heat without actually cooling the air around us—in humid Singapore.

These innovations will reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, but they may take years to reach markets and change enough minds about what it means to cool people down.

For now, energy-efficient air conditioning units remain the most effective approach. According to the International Energy Agency, improving energy efficiency will count for nearly 40 percent of the emissions cuts needed to keep global temperatures from rising above 2 degrees Celsius—beyond which climate change’s effects get far worse. Cooling needs count for much of this load. In ASEAN, using energy-efficient cooling would cut electricity consumption by 100 terawatt hours: the annual output of 50 coal power plants.

Given that the most efficient air conditioning units are up to 30 percent more efficient than their competitors, a widespread shift to this technology will lead to huge cost and electricity savings, particularly in Thailand and Indonesia. But most people may not be aware of the energy label and ratings systems in their countries—or how much using energy-efficient units will impact climate change. Seven out of ten Southeast Asians surveyed feel that better consumer awareness campaigns that help people understand the savings brought by more efficient air conditioners would help.

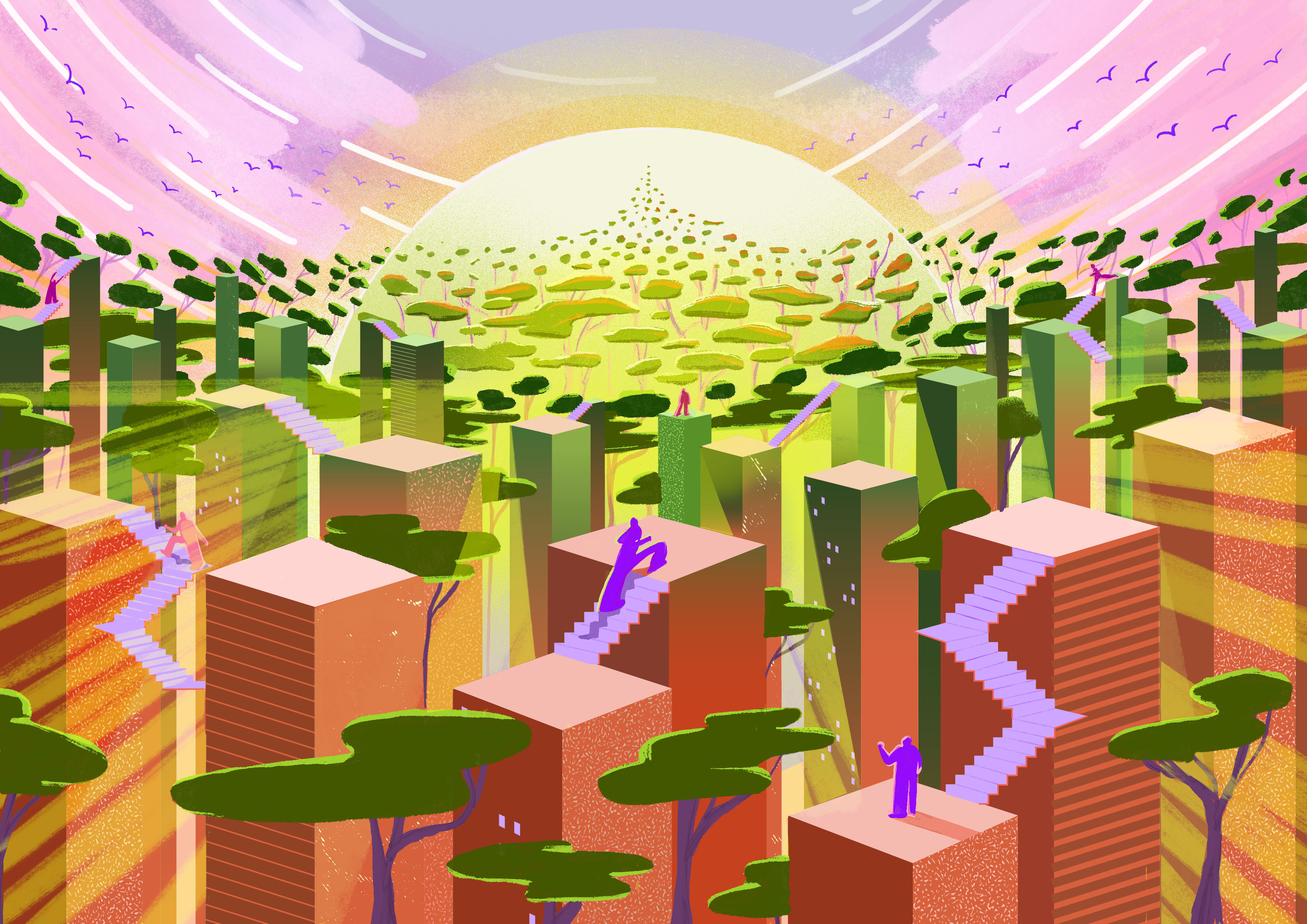

In the long run, buildings that heat up less in the first place and that use passive cooling instead of air conditioning seem poised to become a crucial pillar of green architecture. Many passive cooling techniques, which have steadily gained recognition in architecture communities, come from traditional or vernacular building practices in the region.

That said, tropical Southeast Asia has its own challenges for passive cooling. The region’s high humidity makes cooling by evaporation way less effective; in fact, cooling systems must dehumidify indoor air so that people can feel comfortable and condensation doesn’t form indoors. Persistent cloud cover and small changes in diurnal temperature also make methods that rely on cool nights and hot days (e.g., radiant cooling and ground coupling) less effective.

For this reason, buildings in the tropics tend to favour cooling through a mix of shading, ventilation, and vegetation.

Sun shading using an overhang, a common technique in the tropics.

Overhangs, louvers, awnings, and trees block the sun’s heat, cooling indoor environments considerably. They improve natural lighting quality within buildings, though their design must consider their building facades’ solar orientation.

Cross-ventilation and stack ventilation in a modern building. Adapted from Mogave Architects.

Wind blows through vents on two sides of a building (cross ventilation), and warm air rises and exits the building through ceiling vents, pulling cooler air in from below (stack ventilation). Cross ventilation in the tropics relies a lot on wind force, and it does best with buildings designed to optimise this. It’s also more effective here than stack ventilation, as indoor and outdoor temperatures are not drastically different.

Illustrated example of rooftop plant cover. Adapted from MIT Climate CoLab.

Vegetative cover absorbs sunlight’s energy for evapotranspiration and photosynthesis, cooling and shading buildings during the day. The plants’ drainage layer, a gap between the vegetation and the roof beneath it, helps remove water from tropical thunderstorms while also insulating the building from outdoor heat. Plant cover also helps mitigate carbon emissions, beautifies rooftops, and provides opportunities for urban farming.

As passive cooling requires significant planning and technical knowledge, these changes will take decades to fully transform our cities. Given the sheer demand for air conditioning in the region, even energy-efficient AC units still produce large amounts of greenhouse gases when taken together, making passive cooling a necessary part of Asia’s urban sustainability solutions.

Thankfully, ASEAN states are already moving to cut air conditioning emissions right now. In 2015, the ASEAN Ministers of Energy Meeting endorsed a roadmap with mandatory minimum energy performance standards for air conditioning units. Just three years later, the average efficiency of all air conditioners in Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, Vietnam, and the Philippines were 15–30 percent better than these standards.

Industry experts suggest that governments should encourage the use of efficient air conditioning units through campaigns, rebates, tax rebates, and loan financing. That said, the diversity of development stages in Southeast Asia means that each country needs its own approach. As smart cities grow in Asia, urban planners and administrators must find ways to monitor cooling needs and equitably integrate efficient AC units into our cities.

Over the past several years, ASEAN governments have grown very interested in green building techniques and standards. Many member countries now have their own green building standards and rating tools, several adapted from the United States’ Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating system to reflect local considerations.

Tools such as Singapore’s Green Mark are a great start to making sustainable architecture the new norm. However, they also often still consider air conditioning an essential part of building design. In the long run, governments must play a key role in changing the norms and regulatory guidelines around passive cooling in the building construction industry and among their citizens.